Transparency in today’s globalised healthcare world has impressed governance with the necessity of becoming increasingly accountable for patient safety by introducing quality standards and methods in order to retain a competitive edge and attract market share.

In any complex organisation, it is the role—and the responsibility—of the leadership to set standards for performance. This responsibility is especially important if healthcare organisations are to succeed, both clinically and financially. The governing body, as representatives of the community, must support processes for patient safety to be monitored and improved, and it must hold the administrative and clinical leadership accountable for good outcomes and quality care. Moreover, globalisation of healthcare services and competition for market share are encouraging standardisation, transparency and the use of measures to objectify the delivery of care. Governing bodies can no longer rely on CEOs or medical leadership to provide the impetus for improvement efforts.

A central myth of healthcare—that doctors should not be questioned—must be reevaluated and exposed as antiquated. Today, doctors have to respond to the patients who insist on the best care and to leadership who insists on returning value for expenditure. In the US, government agencies and private groups are forcing physicians to document that they are delivering specifically defined indicators of care for specific patient populations. Further, the myth of the all-knowing doctor is diminishing as the media highlights the vulnerability of patients in the nation’s hospitals.

In my experience educating healthcare leaders in various Asian countries, I have been struck not only by the variation in governance structures but also by the lack of clear lines of accountability for delivering safe, effective and efficient care. Many of the best healthcare organisations are looking to introduce quality management infrastructures into their institutions and to incorporate evidence-based medical standards of care in order to compete on an international level and assure the public that their organisations provide excellent care. Several of the organisations where I consult, are looking to become accredited as a way to promote standardisation of care. Many of the leaders I meet ask for education and guidance about how to introduce these cultural changes into their hospitals and implement improvements. As part of the curriculum in educating CEOs in China and elsewhere, I instruct them on the role of the governing body, and of accountability as a tool to improve organisational performance and change clinical outcomes. In a recent visit to Singapore, I gave a workshop to physicians and nurses on the value of using statistics to improve the quality of care and promote a safer environment at the bedside.

Once the governing body commits to its oversight responsibilities, both fiduciary and clinical, I encourage them to adopt quality management principles and methodologies to implement patient safety improvements. Through measurements of the specifics of care and through aggregated data reports, governing bodies can learn to effectively manage the complexities of clinical care and organisational processes. Improvements are implemented when members of the governing Board learn how to ask questions of the medical staff, gain experience understanding quality reports, evaluate how resources should be most productively spent, and make informed decisions about improving care. When the clinical staff receives strong and effective guidance from the governing body, individual agendas collapse and organisational goals become the yardstick for success. A strong and unified Board should empower the quality management department in their organisation to develop measures to monitor care, train staff on how to collect data regarding those measures, aggregate and analyse the data for trends that reflect opportunities for improvements and best practices, and develop high level reports to inform the Board on an ongoing basis about how care is delivered and processes managed.

When leadership actively supports quality and the use of data to standardise, monitor and improve care, staff are compelled to view care as a complex process managed by a team that must effectively communicate with each other rather than use an individualised and idiosyncratic approach. As quality data gets collected regularly and reported, the Board becomes increasingly familiar with understanding the processes of care. They can begin to hold clinicians accountable for errors, gaps in care and adverse events, and begin to develop a proactive approach to medical error prevention, thus changing the culture.

For example, when cardiac mortality was reported as high in one of the hospitals I work with, the Board charged me to discover where the process of care was flawed and to develop improvements, monitor those improvements for effectiveness and report back to them. It was the Board who insisted that processes be changed, and the Board that supported new processes. Working with a multidisciplinary team, consisting of clinicians, administrators and quality professionals, we were able to decrease cardiac surgery mortality and become one of the best cardiac surgery departments in the state. The CEO alone could not have effected the change, nor could an individual physician. Change required aggressive action on the part of the Board, who took their oversight responsibility seriously.

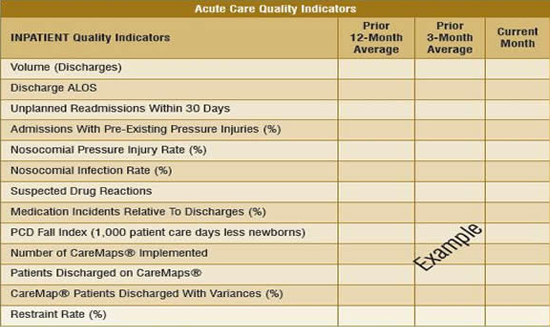

Once leadership commits to the oversight of patient care, a method has to be adopted to best communicate information from the bedside to the Board about the provision of patient care services. Data provide an effective communicative tool to encourage trust between governance and clinical leadership. With expert input from clinical staff, quality management developed a Table Of Measures of quality indicators about clinical and organisational processes (Table 1) that were regularly reported to the Board.

Not only could the Board monitor census data such as volume, but also patient safety indicators such as falls and nosocomial pressure injury rates as well as proactive safety methods such as the number of patients on clinical guidelines or CareMaps, and the number of near misses reported about medication errors. Tables of Measures were developed for various levels of care, such as behavioral health, ambulatory care, long-term care and the environment. Through the means of data, the governing board was able to oversee care, and ask questions when variations were evident. Without quality data, they would have had no means to carry out their responsibility for oversight of patient care.

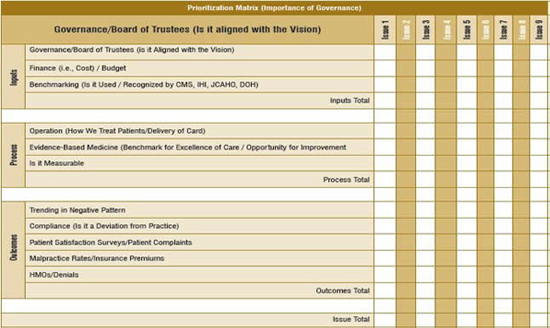

Because the Board had the responsibility to evaluate competing areas for improvements, we developed a prioritisation matrix (Table 2) to help them weigh which improvements were most pressing.

This tool enables members of the Board to make responsible decisions about how to allocate resources. Once an improvement has been identified as a top priority, steps can be taken to implement new processes.

For example, if the leadership of the organisation determines that it is their priority to reduce the rate of hospital-acquired infections, how can they go about making this happen? One useful method is to ask the people closest to the problem for their input about the present process, potential problems and suggested solutions. Multidisciplinary task forces should be established with a physician champion as the leader to determine what processes need to be improved and establish accountability for those improvements. Measures then need to be carefully established with appropriate numerators and denominators. If central line infections are being monitored, the measure might be defined as the number of patients who contracted central line infections over the number of all patients who had central lines inserted during a specified period of time. Once the measure is defined, data has to be collected, either retrospectively or concurrently, and reported to various members of the organisation. The task force can suggest improvement efforts; perhaps introducing an improved sterilisation procedure and then monitor if that improvement has been effective. These cultural changes do not happen overnight. They take time.

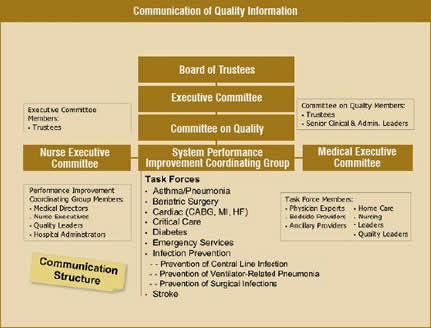

Finally, without an established effective communication structure, information cannot be used for improvements. Organisations should establish lines of communication that go from the front line staff to the people responsible for oversight (Table 3).

Quality management should work with clinicians and administrators to form performance improvement committees that coordinate information with clinical leadership to report to the governing body. The communication must be bidirectional, with members of the Board interacting with clinicians and front line staff, asking questions and hearing firsthand about problems in the delivery of care.

Through these processes and with improved education to the governing body, care can be standardised and patient safety issues promptly recognised and addressed. By creating an effective governance structure, the relationship between governance and clinicians can be redefined to create improved processes that will enhance patient care delivery. Open communication will foster cultural change within the organisation and promote a proactive approach to patient safety.