Healthcare organisations are redefining value and have been forced to think in new ways about the process of care delivery.

During the past few years the concept of value in healthcare has changed dramatically. It has evolved from considerations of profit based on volume of patients and number of procedures to an environment where profit is increasingly connected to quality outcomes. The government is not only increasing reimbursement for good outcomes but refusing to pay for care that is inappropriate or where outcomes fall below established benchmarks. Healthcare organisations have been forced to think in new ways about the process of care delivery; leadership has begun to assess the value of the care delivered, that is, leadership is concerned about the relationship of quality care to cost/expenses and patient/customer satisfaction.

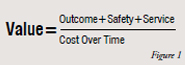

Healthcare organisations are redefining value. For example, in their orientation booklet, the CEO of the Mayo Clinic, Denis Cortese, has summarised how senior leadership defines value by an equation

This premier healthcare institution defines value as more than good outcomes and lowered expenses. Their definition of value also incorporates patient safety and good service, and in doing so integrates concepts that can define the vision of the organization. Value involves quality care, lowered costs, patient safety and satisfaction with the experience. This concept is very different from one stressing volume.

Michael Porter, a healthcare economist, in a perspective article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Dec 23, 2010; N Eng J Med 363;26) has defined value as “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent” (p.2477). Value encompasses more than cost reduction; it centers on patient outcomes, that is, the positive results of the care delivered. In the June 2011 issue of the Healthcare Financial Association Magazine (http://www.hfma.org/hfm/) value was said to be “driving a fundamental reorientation of the healthcare system around the quality and cost-effectiveness of care (p.1).”

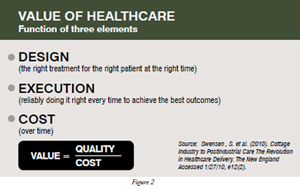

Another article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Swensen, S. et al (2010)) defines value as a function of three elements:

Designing the right treatment for the right patient at the right time and delivering the treatment in the right way represent quality aspects and will increase value and lower cost over time.

Shifting the concept of value from volume/utilisation (i.e. how many patients, how many services, case mix index) to outcomes/results that can be documented as effective, safe, and appropriate is a new framework, one which all stakeholders, patients, providers, payers and policymakers embrace. Value has the goal of improving outcomes as efficiently, and as cost effectively as possible. This concept of value can be quantified. Data collected about outcome measures should show the results in comparison to the defined benchmark. Safety can also be quantified. Variables such as infection or nursing sensitive measures, such as decubiti, can be measured as can the morbidity and safety standards formulated by The Joint Commission. Service can be quantified as well. Government programmes, such as the Hospital Care Assurance Program (HCAP) compensate hospitals that document that they are caring for underserved populations. Therefore, value is no longer a subjective concept but an objectively definable one.

This changed concept of value affects every aspect of the hospital organisation. The C-suite (i.e. CEO, COO, CFO, CNO) has become invested in and involved with quality data because that data not only has a relationship to reimbursement but also because quality data is available to the public and influences market share. Healthcare organisations are compared on public websites (e.g. Hospital Compare, Health Grades) that display quality data such as risk-adjusted mortality rates and other variables, enabling the healthcare consumer to make informed choices about where they want their healthcare dollars to be spent. As the availability of data increases, the public concomitantly expects good outcomes, that is, value for their expenditure. This is true for all healthcare organisations globally, not just those in the US. According to Fred Stevens, in The New Blackwell Companion to Medical Sociology (2010) healthcare should be considered a “commodity that can be bought or sold on a free market” (p.447).

As reimbursement policy begins to change and as insurance companies demand efficiency, productivity, and optimal results, and as they refuse to pay for poor outcomes or waste, the notion of value in healthcare is measurable through data. In the future, hospital data that reveal rework, such as reoperations, readmissions or never events (i.e. errors, such as wrong-site surgery, which should never occur and are preventable) will not receive payment. Insurance companies will pay more for good results.

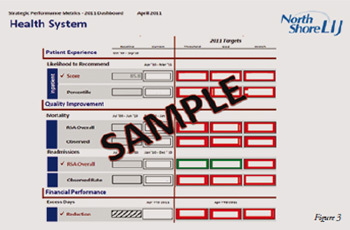

Administrative leadership, responsible for the budget, is becoming increasingly involved in pursuing good results, the traditional purview of the physician alone. The focus on value is dependent on ongoing cognitive change, improving health not only for individual patients but for specific disease populations. Quality care requires open communication across the continuum, shared goals, teamwork, and increased accountability for performance. Quality data reveal value, from mortality rates to customer satisfaction. In the North Shore – LIJ Health System which is comprised of 15 hospitals and over 200 ambulatory care centers, the CEO, Michael Dowling, encourages all providers to be accountable for outcomes. He knows that the better the results are, the lower the costs and the greater the reimbursement will be. His executive leadership monitors value on an ongoing basis through the dashboard that displays clinical and financial indicators in one matrix (See Figure 3). The combined indicators alert the CEO, CFO, CMO, CNO and COO to issues related to value and quality. The value-based purchasing programme that the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is promoting will provide incentives to hospitals that exceed certain quality measures relating to clinical care processes and the patient experience.

The US government is also helping to drive new concepts of value. CMS has defined measures that result in increased reimbursement as well by financially rewarding organisations that are in the top decile of achieving compliance with performance measures, including core measures such as aspirin administration to heart attack patients. In order to reach the top decile and to maximise reimbursement opportunities, healthcare organisations have to establish robust and sophisticated quality management programmes. In the past, even if caregivers did not comply with hand hygiene protocols and patients acquired infections, the hospital still received payment for interventions, such as ICU care or for the increased length of stay (LOS) required to treat those infections. Today, caregivers are accountable for hand hygiene compliance and infection rates are monitored to ensure compliance and a short LOS. Current and future reimbursement will be based on patients receiving appropriate treatment and not for the consequences of poor care which endangers patient safety. Financially lucrative transplant programs can be closed down if good outcomes such as survival rates do not meet expected rates.

Due to the increased expectation of insurers, the government, and administrative leadership, care providers have become more accountable. It is no longer sufficient for clinicians to argue that their patients are sicker than others or that the excellent education that they have received is sufficient to ensure quality outcomes. In today’s world where value is measured, there has to be data to support such claims. Physicians need to justify variation from the standard of care and are expected to base treatment on evidence and deliver care that exceeds expected benchmarks. Poor outcomes reflect poorly on both the caregiver and the institution. As the computerised medical record becomes integrated into healthcare organisations, leadership will be able to easily monitor the appropriateness and effectiveness of care and services of individual physicians. Therefore, physicians are under pressure to change care processes so that data reveal the value of their care.

In addition, the focus on increased accountability and transparency has caused physicians to become more active in managing the specifics of care and responsible for ensuring that that care is cost effective as well as efficient and appropriate. They are using data to ensure that their care is consistent with evidence based medicine and that their patient outcomes can be favorably compared to those of other clinicians. Again, value is definable, measurable, quantifiable, and verifiable.

Under the previous reimbursement system, hospitals were paid for performing procedures, such as surgery. The procedure was not evaluated for appropriateness. Today, procedures are evaluated for appropriateness and if it is determined that the procedure was either unnecessary or ineffective, payment will be reduced. In other words, the value of the procedure to the patient has to be proven. For example, patients who experienced back pain were often recommended for surgery. The hospital and the physician received payment for the surgery. Today, payers question whether surgery is the best option for the patient’s condition and whether or not it is effective.

Many traditional and accepted procedures are being reevaluated for value.New questions are being asked. Is orthopedic surgery on knees providing patients with the best value? Do heart patients benefit more from medication or stents or open heart surgery? Is new technology necessary and effective? For example, is robotic surgery superior to manual? Is the expense of purchasing and training physicians to use robotics an efficient use of resources? Value takes into account cost factors, effectiveness and appropriateness and these variables have to be argued and proven with data, not subjective experience. Value means that the patient and the healthcare organization get the best return on their investment. Services and procedures should be neither overused nor underused.

In the North Shore – LIJ Health System,risk-adjusted mortality rates for cardiac surgery were monitored for over ten years. As new processes were introduced and quality standards integrated into the process of care, mortalities decreased dramatically. The value of having the best results in terms of a physician’s or a service’s performance increases market share. When the public is informed that the volume is high and the mortality rates below the expected benchmark, the organisation maintains a competitive edge and gains in prestige.

To achieve good outcomes, improved processes had to be integrated across the entire continuum of care, from admission, to pre-operative, post-operative and discharge phases. Multidisciplinary teams examined the medical charts of those hospitalised patients who had died and realised that there were opportunities for improvement. Defined assessment criteria for patient appropriateness were formulated. Consistent variables were defined, databases were developed, which defined expectation and improved communication among the different caregivers. Silos that traditionally separated the continuum were eliminated. All care providers were required to participate in improvement efforts. Because conscious efforts were made, and interventions established based on using the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) methodology, outcomes improved. With good results, waste is decreased. Therefore, fewer readmissions and reoperations occur, infection and mortality are reduced, and the ICU is more efficiently utilised. Value is generated when results are good and communicated to the public.

Value is more complicated a concept than simply lowered cost for services. Leadership has to determine which processes result in good outcomes and then analyse the cost of the intervention to determine its value. Focusing on value rather than volume is forcing medical care to change. Among the challenges healthcare reform faces to ensure superior value for services is changing the current milieu. Practicing physicians are reluctant to change the way they practice medicine and adopt a value-based perspective determined by standardizing care and data regarding outcomes. Of critical importance is that new physicians be educated to meet expectations of a culture focused on delivering value. The Krasnoff Quality Management Institute of the North Shore – LIJ Health System has embarked on curricula development to effectively educate physicians including residents and fellows, as well as healthcare administrators and providers, on improving quality and the efficient use of resources. Patients need to trust their physicians and the healthcare system at large. Until physicians are able to execute these changes, the full achievement of a true value based system cannot be achieved. Increasing value, then, is dependent on the perceptions and behaviors of physicians, insurers, governmental leadership and the general population. If healthcare costs are to be responsibly contained while improving quality, future efforts must support adaptability and the means to meet this challenge and ensure a value driven healthcare system.

Author BIO

Yosef D Dlugacz has decades of experience dealing with process variables and educating professionals and the community about the importance of integrating quality management methods into the delivery of care to improve health outcomes. Dr. Dlugacz has educated thousands of professionals in Quality Management philosophy and techniques nationally and internationally. He is an Adjunct Professor of Quality Management in the Baruch/Mt. Sinai MBA Program in Healthcare Administration, an Adjunct Professor of Information Technology and Quantitative Methods and Professional Faculty Coordinator of the MBA Program in Quality Management at Hofstra University, a Visiting Professor to Beijing University’s MBA Program, and an Adjunct Associate Professor of Medicine at the New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY.