Benchmarking and Accrediting in Health Informatics

Driving up quality and reducing risk

Quality assurance and continuous development of health information and IT services in healthcare is a key patient safety and business issue. A part of this is the need to assure the professionalism of individual practitioners as well as the services themselves.

Information has always been at the heart of healthcare delivery. Today, new information systems and technologies are becoming ubiquitous in health and give rise to new opportunities and challenges to the ways care is delivered and the way professionals work. Information sharing between professionals, care providers and sectors; and patient access to and management of their own records are driving changes in inter-professional relationships and care delivery processes.

So, information and information systems underpinned by technology are increasingly impacting directly on patient experiences of healthcare delivery and on their treatment and on the outcomes of their care. There is, as a result, an increasingly vocal group of professionals in health who would argue that if information, information systems and IT can positively impact upon patient care, then the converse must also be true. The UK Council for Health Informatics Professions (UKCHIP) has collected a catalogue of examples of healthcare delivery failures where information and IT systems are implicated in errors and even loss of life. Our information and IT systems, therefore, need to be safe; and the professionals—individuals and teams, who design, implement, support, manage and develop these systems must also be assured, as far as possible, as safe to practice. In an increasingly litigious world, is this an issue healthcare delivery organisations can continue to ignore?

Further, commercial pressures, whether in State—funded healthcare services which exists in the UK or private or insurance-based services (or indeed a mixed health economy)—have an obligation to deliver best value, high quality services that demonstrably use accepted standards and be committed to the principles of continuous improvement. Commissioners of services want to know they are buying a quality, value for money service; and service deliverers want a competitive edge in an increasingly pressured free market. In England, a further driver in the push for benchmarking and accreditation of both informatics practitioners and services and teams has been a continuing concern that recruitment and retention in informatics in health is problematic and that we just don’t have access to the right people with the right skills. When we find and appoint staff, the employment package is not sufficiently attractive to retain the best. Whilst there is a perception that pay is not as high in the public sector as it might be in the private sector, it is actually lack of status and lack of opportunities for career progression that drive staff out into the more lucrative private sector.

In the UK, UKCHIP now holds a professional register of some 700+ individuals and is in the process of applying for accreditation by the UK Accreditation Service which will authorise it to certify professional status. This will require a revision of existing standards for and levels of registration and further contribute to driving up quality and providing assurance to employers that staff are safe to practice having not only met the requisite standards but agreed to abide by a code of professional conduct and created a planned programme of continuous professional development.

IT and informatics are relatively young professions and are in the formative stages of development. They are sometimes criticised for not making faster progress but recent developments in English national informatics strategy indicate that the tide may be changing. There are a number of actions that could speed up progress, foremost of which are:

1. Giving informatics a place on Executive boards with a CIO type post reporting directly to the CEO

2. Organisations should expect professional accreditation/registration and include this in job descriptions and person specification

Developing an approach to benchmarking and accreditation of health informatics services

Let us move away from discussing the accreditation of informatics practitioners as individuals, to consider a range of issues associated with the benchmarking of health informatics services and teams.

Benchmarking or accreditation?

The nature of the political environment and the strategic drivers for a scheme will influence decisions about whether either benchmarking or accreditation, or both, are required. Benchmarking may well be the first stage of a process of accreditation, enabling teams and services to assess themselves against a set of measures and metrics in a non-threatening environment; and to share the outcomes only with selected peers and colleagues; or more widely in an anonymised or pseunomynised form. This implies that outcomes may not routinely be shared with commissioners and purchasers of services and may arguably have limited value from these perspectives.

With benchmarking there is generally no ‘pass or fail’ and the process may, therefore, be seen more developmental and less threatening than a formal accreditation scheme.

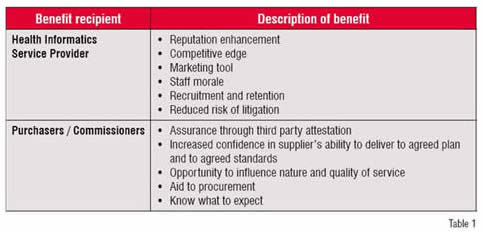

Table 1 summarises the high level business benefits of an accreditation scheme to both providers and commissioners / purchasers of services.

Voluntary or mandatory?

Whether an accreditation scheme should be mandatory or voluntary is again a potentially contentious issue for some of the reasons set out above. It may well be the case however from the perspectives of both commissioners / purchasers of services and service providers themselves that a requirement to go through a process of assessment is desirable in the interests of patient safety and continuous improvement; but this is not the same as saying that a scheme should be mandatory and that services will be classified according to an agreed scoring system. The implication of the latter is that a service or team might be deemed unfit for purpose or ‘unsafe’ and accordingly lose its ‘licence to trade’. Again, the political and commercial drivers for the scheme will dictate the preferred approach. Experience from other UK public sector approaches to accreditation in healthcare undertaken by organisations such as the English NHS’ Healthcare Commission suggests that an incremental approach to scheme implementation and development are more likely to receive the support of participating organisations and, therefore, more likely to achieve scheme objectives.

A generally well-respected and well received scheme in England has been the Pathology Accreditation Scheme which combines an accreditation scheme with integral peer review and support for improvement through a programme of action learning to support service modernisation and continuous improvement, and the establishment of pathology (people) networks.

Existing standards; measures and metrics?

Researching existing approaches to benchmarking and accreditation in the chosen domain is essential in the interests of time and resources. Avoiding duplication is essential.

Checking out what standards, measures and metrics already exist will not only save time and ensure appropriate links and connections are made with other complementary schemes; but will make the task of scheme members less burdensome. If an organisation already has been through a process of accreditation to, for example, ISO 9000, any accreditation scheme comprising a comparable standard should accept a statement of compliance (to be supported by evidence if required) as sufficient for its purpose. Reference to existing standards either as guides to good practice or as required evidence of quality should be built into a scheme and references to sources of information and support be made available within the scheme.

Measures and metrics should also be both clearly defined and meaningful to stakeholders. In designing any assessment tool, stakeholders—service providers and service purchasers / commissioners—should be involved and the tool tested in a robust way to ensure sense, appropriate use of language and ease of use. A simple glossary to help define terms might help avoid misunderstandings and a loss of credibility for the scheme and its content further down the line; as will testing and piloting in a cross section of organisation types and environments.

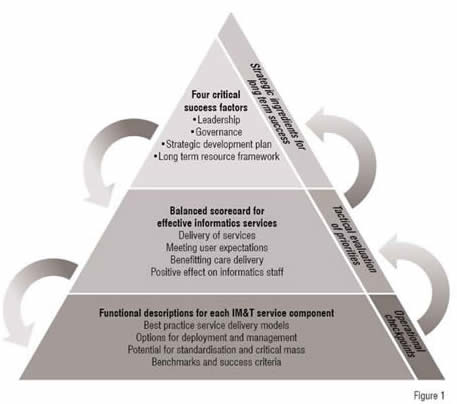

A high level description of the tool developed in England is provided below. Behind the framework is an online tool comprising 300+ measures and metrics. It started life as a complex and macro-rich MS Excel spreadsheet and is in the final stages (early 2009) of conversion into a web-based tool flexible enough to support the assessment of services and teams, from those delivering the full range of informatics services (including information management and training and development) to those delivering just some of the possible elements of service.

Conclusion

Quality improvement and value for money, together with large scale investment in health informatics systems, are at the heart of the need to ensure effective, efficient and safe health informatics services available to support clinical professionals twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, 52 weeks of the year. The accreditation of individual practitioners, teams and services to agreed national / international standards are themselves at the core of service improvement goals.

In the English NHS, a Health Informatics Service Benchmarking Club has been established with support from NHS Connecting for Health but owned and managed by the constituent members (over 100 services have joined the Club at the time of writing). The next phase of the development, during early 2009 will be to appraise a number of modes and models of accreditation already in existence and to consult service commissioners and providers on the business benefits and merits of a national accreditation scheme. If such scheme is supported and there is optimism that this will be the case a service provider will be procured during 2009 with a view to the scheme becoming live in 2010.