Digital Health refers to innovative initiatives that leverage digital technology to achieve a desired outcome in the healthcare industry. Currently, there is a mainstream shift of investment from maturing technologies such as telehealth and mHealth to new fields such as AI and VR. The process of commercialising digital health should begin from identifying the end objectives.

Many market research reports estimate the global digital health market in 2018 to be worth around US$200 to US$300 billion. Supposing these estimates are correct, the size of digital health market was between 20 per cent to 40 per cent of the size of the global pharmaceutical market (US$800 billion) in that same year. Yet, one would be hard-pressed to readily name a business that best represents this enormous market. Has the digital health industry produced a world-class business in the same vein as Pfizer or Novartis? Or is digital health a house of cards?

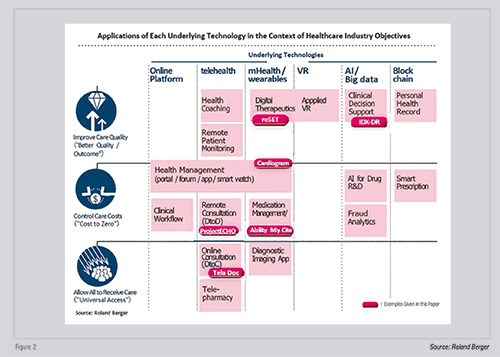

Red-hot digital technologies such as telehealth, mHealth, AI, VR, the blockchain are strong candidates with the potential to bring further innovation to the healthcare industry. Indeed, countless long-standing players are going through gradual process of trial and error in their bid to identify and define the roles that these technologies will serve in the market. The commercialisation of digital health technology should begin from each company defining a desired outcome that it wants to achieve, followed by a consideration of how and which digital technologies to best leverage.

In 2017, the US Food & Drugs Administration (FDA) gave its approval for the first Prescription Digital Therapeutic toreSETdigital therapy, developed by Pear Therapeutics as a single treatment for dependency on alcohol, narcotics, cocaine, and stimulant drugs. Aimed at treating addiction, reSET encourages modification to a patient’s behaviour through communication with the patient via an app. As a follow-up to reSET, Pear Therapeutics has applied for, and is awaiting approval on, reSET-O, a combined therapy for opioid dependence. Furthermore, clinical trials are underway on other digital therapies such as Virta Health’s treatment aimed at diabetes patients and Propeller Health’s treatment for asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases (COPD) patients.

Pear Therapeutics, Virta Health, and Propeller Health are a few of the many companies that develop digital therapies. When thinking about the development of digital therapies, one might imagine a process much like the development of an iPhone app. However, these businesses have internal structures that bear much closer resemblance to those of a pharmaceutical company, withre search teams, clinical development teams, quality assurance groups, and pharmaceutical affairs groups.

It has been some time since digital health was heralded as one of the megatrends in the healthcare industry. Initially, most attention focused on technologies such as telehealth, commonly typified by remote medical servicing, and mHealth, which makes extensive use of apps and smartwatches. Increasingly in recent years, investment has begun shifting to new fields such as AI and VR. Market entry activity into digital health has also increased and, through continued offerings of new products and services, the strengths and weaknesses of each underlying technology become more evident.

In this issue, we will first look back at megatrends in the healthcare industry; second, lay out the positions of each technology in digital health industry where before they tend to be considered in isolation; and third, identify what roles they could accomplish in the healthcare industry. In doing so, we hope to answer the question of whether digital health can be a viable business.

It is difficult to generalise about the entire healthcare industry. The players active in this industry constitute an incredibly wide-ranging group of companies that includes manufacturers such as pharmaceutical companies and medical device manufacturers; service providers such as medical institutions including hospitals and clinics, specimen laboratory operators, and pharmacies; the insurance companies that hold decision-making power over reimbursements for medical bills; and finally wholesalers of medical supplies and providers of systems to medical businesses and institutions. The market is further complicated by differences in health policy, regulations, and insurance regimes from one country to the next. Thus, strictly speaking, trends will vary by country and by player.

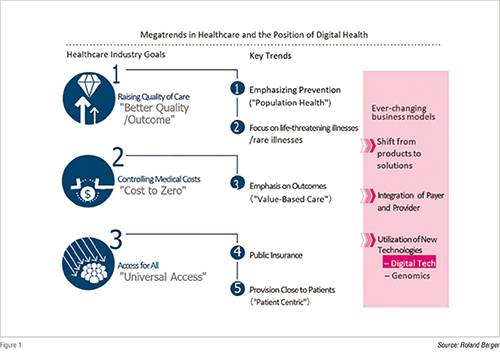

Nevertheless, long-term inclinations of the healthcare industry fall roughly under three categories. These three categories are: better quality (improving quality of medical treatment), cost to zero (reducing costs of quality treatment so that anyone can receive it), and universal access (allowing all to receive quality treatment). see figure 1.

The megatrends of the healthcare industry are always aligned with how to transform the industry further to achieve those three objectives. For example, pharmaceutical companies’ focus on drug development for lifethreatening or rare illnesses is one conspicuous effort towards raising the quality of care. At the same time, progress made in consolidating public insurance into national insurance schemes in developing nations like China and Indonesia represents an initiative aimed at improving access to medical treatment.

Nowadays one frequently hears about ‘population health’ or health maintenance for social groups, which represents an effort to control medical expenses by preventing illnesses before they occur. Similarly, “value-based care” or otherwise known as pay-forperformance care aims at improving quality of treatment by focusing on patient outcomes; pursues the delivery of quality care to many people through price (reimbursement) setting that accounts for improved results on patient outcomes.

Between these three objectives, what gets prioritised varies according to country, player, and field of medicine. For example, in developing nations with nascent medical infrastructure or health insurance systems, improvement to access is likely the foremost issue. In various fields of medicine, improvement in treatment quality is sought, especially for diseases like Alzheimer’s where satisfaction is comparatively low. By comparison, in the field of hypertension treatments, there is stronger emphasis on the promotion of generic drugs in the interest of trimming costs. Researchbased pharmaceutical companies aim to develop new drugs that improve the quality of care, while manufacturers of generics seek to contribute by controlling costs of healthcare.

Dr. Sanjeev Arora of the University of New Mexico launched Project ECHO (Extension for Community Health Outcomes) in 2003 as a telehealth platform that facilitates the online exchange of information between physicians specialising in hepatitis C and clinics around the state. At the time, only 5 per cent of hepatitis C patients in New Mexico could receive appropriate treatment. The lengthy patient waiting-list for Dr. Arora, who was one of just two specialists in hepatitis C in the state at the time, could result in waits of up to eight months. Following the launch of the project, this wait time was shortened to just two weeks.

Subsequently, 3,000 medical institutions in New Mexico alone joined Project ECHO and, as its coverage expanded beyond hepatitis C to circulatory disorders, chronic pain, dementia, endocrine disorders, HIV, and mental illness, the project came to contribute to the treatment of more than 6,000 patients. The exchange of ideas between general practitioners and specialists via the platform allowed patients to receive cuttingedge examinations and treatments on par with those offered by a university hospital, even at their local clinics. According to the paper submitted in 2011 to the New England Journal of Medicine, ECHO achieved a treatment success rate equivalent to that of a university hospital.

Currently, the project has proliferated, not only throughout the United States at hospitals such as MD Anderson and University of Massachusetts, but it has also come into use overseas, in countries such as Uruguay, India, and Canada. ECHO is just one example of how telehealth, in the form of a D2D (doctor-to-doctor) communications platform, has secured results.

Compare to the platform provided by TelaDoc, launched in 2002, to connect doctors with patients (D2P). TelaDoc is a 24-hour service that allows non-emergency patients to consult by phone with physicians, receive online examinations including those by specialists, and obtain prescriptions for basic medications. Around one million ‘visits’ were performed on this platform by 2016.

TelaDoc has expanded its business by broadening its platform, which focused on individuals, to target employees of multinational corporations. At present, it is the largest telehealth operator in the world with 7,500 client businesses and 20 million members, and it boasts of a 95 per cent customer satisfaction rate. It acquired Advance Medical of Spain in 2018 and has proceeded into the field of private medical insurance in Asia and South America, broadening its expansion to 125 countries worldwide. After going public in the US in 2015, its value has seen favourable movements and its market capitalisation exceeds US $4 billion.

As we can see in the above two examples, telehealth in its D2D and D2P forms, can play an active role as a platform to secure patient satisfaction, even in communities that are difficult for specialists to reach, by facilitating effective treatments that are similar to actual visits to specialists. Moreover, there have been recent examples with results surpassing those of actual doctor visits. One telehealth provider has described a case in which mental health patients and pediatric patients, who find it stressful to meet directly with a physician and thus tend to put off visits, could be seen by physician via telehealth technology.

Meanwhile, one advantage of mHealth is how it enables the realtime, continuous collection of data and monitoring of patients. If this technological enablementis leveraged to its maximum extent, mHealth can demonstrate an impressive value in the aspect of improving medication compliance and in preventing disease.

According to the Annals of Internal Medicine, the percentage of patients who take their medication as prescribed is under 50 per cent, and the resulting losses are estimated to reach US$100 to US$300 billion. mHealth has so far demonstrated solid compatibility with this sector: there are innumerable services that alert patients by mail or smartphone notification to take their medication. Moreover, in November of 2017, Abilify MyCiteby Otsuka Pharmaceuticals and Proteus USA gained approval from the FDA as the world’s first ‘digital pill.’ For Abilify MyCite, a sensor is embedded in the drug Abilify, which has already been approved as a treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This sensor then transmits data to the patient’s smartphone when the patient takes their dose. When the patient shares this data with their physician, the physician can check on the effectiveness of the treatment and make changes to the treatment plan based on data concerning the administration of the drug. By sharing this data with family members, the patient can further avoid forgetting to take their medication.

At the conference of the American Association for the Advancement of AI (AAAI) in February of 2018, research was presented in which patients with a history of diabetes were detected with an accuracy of 85 per cent using the heart rate monitor of an Apple Watch. The team announced that Cardiogram has so far been able to detect arrhythmia with 97 per cent accuracy, sleep apnea with 90 per cent accuracy, and hypertension with 82 per cent accuracy by combining of the heart rate monitor of the Apple Watch with the team’s machine learning algorithm. While these data are insufficient to make a decisive diagnosis, they could lead to early detection and prevention if they can encourage high-risk patients to have exams performed by physicians.

The roles of telehealth and mHealth have become considerably clearer with the arrival of platforms expanding around the globe, companies going public, and products gaining FDA approval. As these roles have come into view, the greatest issue that businesses face now will be whether they can get insurance companies to reimburse these digital treatments. Though many insurers have acknowledged the roles of telehealth and mHealth, they have doubts with regards to treatment costeffectiveness. There has been sharp criticism over the lack of cases in which treatment has been completed online and whether these technologies merely increase the frequency of medical examinations. ECHO continues to operate with subsidies, while TelaDoc has yet to show a profit at present. Still, TelaDoc’s shift to a model that targets businesses and its entrance into the field of medical insurance via its acquisition of Advance Medical have potential as one business model solution.

While the roles of and issues associated with telehealth and mHealth have become clearer, AI and VR have only recently entered the scene. AI itself, of course, is nothing new for the healthcare industry. The activities of AI in assisting diagnoses, as with IBM’s Watson, are widely discussed. In recent years, however, AI has moved past assistance and into a leading role.

In April of 2018, the USFDA gave its approval for the AI medical device IDx-DR, developed by IDx, as a diagnostic device. IDx-DR takes a photo of a patient’s retina and analyses it with AI software, then gives a conclusive diagnosis of moderate to severe diabetic retinopathy. There have been other AI medical devices which have received approval from FDA, but this is the first time that one has been assessed as capable of giving an exam result without the interpretation of a physician. By using IDx-DR, patients can receive highly accurate examinations unmediated by a retina specialist. Areas of medicine that rely heavily on imagery—not only ophthalmology but also dermatology, radiology, and tuberculosis—have particularly strong compatibility with diagnosis by AI, and chances are good that the process of diagnosing and prescribing treatments in these realms will be revolutionised by AI.

VR has gained significant traction as a technology that could offer new treatment choices for illnesses in which existing treatments have proved ineffective. The largest clinical trial in the world utilising VR headsets has been conducted at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in California. This study, performed in cooperation with healthcare VR leader Applied VR, investigates to what extent the use of analgesics, hospitalisation times, and patient satisfaction in chronic pain patients can be changed through the use of VR. Studies have also shown that pain can be reduced by approximately 25 per cent in chronic pain patients by watching relaxation videos in VR.

VR is particularly anticipated to be effective in the area of mental health for illnesses such as chronic pain, ADHD, and PTSD, where abuse of medications is frequently an issue. As clinical trials using VR are performed worldwide, it would be no stretch to say that the day is not far off when VR takes its place in treatment guidelines as one option for treatment.

Though AI and VR offer great promise, there is still a ways to go before these technologies can penetrate the market. It is worth noting that even if AI and VR secure approval as medical equipment and software, it will be doctors who prescribe them and patients who use them. Doctors and patients may lean towards skepticism over new technologies. Traditional healthcare players like pharmaceutical companies and medical device manufacturers own the full spectrum of capabilities, from establishing evidence, increasing patient awareness, to supporting patients, all of which are necessary to convince doctors and patients. In the future, it is increasingly likely that the AI and VR healthcare industry will make use of collaboration between startups and established businesses, as with the acquisition of Flatiron Health by Roche in February of 2018.

As we have seen, the strengths and shortcomings of the technologies that underlie digital health are becoming apparent. For example, it will be new technologies like AI and VR that have the potential to increase the quality of care by increasing the number of treatment options available. By contrast, expectations are already high for telehealth and mHealth in improving access to care-although it would be too early to conclude the roles each technology will play.

On the other hand, by considering the breadth of the market, we can see that there is a strong likelihood that technology can enable a market to expand worldwide if it is able to contribute to quality of care via digital health. Pharmaceuticals and medical devices have a tendency of spreading as-is throughout the world. By contrast, digital technology's contributions to medical cost controls and access to care must be expanded with consideration over the healthcare systems and medical infrastructure of each nation, and businesses must regard each nation as distinct and respond accordingly. From this perspective, if we simply regard digital health as a standalone business, we may say that the technologies present a large potential to contribute a better outcome for all.

Nonetheless, it will be extraordinarily difficult at the present stage of technological maturity to consider the standalone commercial attractiveness of digital health technologies, given that most of the technologies are still in an early stage of the development. Rather, one should regard digital health not in isolation but instead as an industry that will enable healthcare corporations to reform along their desired lines of objective. Very importantly, we should seek to understand each of these underlying technologies from the standpoint of whether they will or will not contribute to healthcare reforms along the desired outcome. In other words, it would be better to determine the investment area of digital health not by commercial attractiveness but by each corporate vision – by asking where in the healthcare industry would one want to contribute – to achieve the desired outcome.

If we take telehealth as one example, it would be effective at improving access if used to enable online examinations for patients in sparsely-populated areas. Conversely, if it is used as a communication tool linking physicians in remote areas to specialists at university hospitals, it can effectively contribute to improving quality of medical care.

Businesses who wish to prioritise efforts toward improving healthcare access would likely engage in the online examination aspect of telehealth technology, while businesses that wish to improve care quality would engage in telehealth for its doctor-to-doctor communication tool capability. For businesses interested in telehealth, the crucial question to ask is not, “Of online examinations and D2D communication tools, which is more promising?”, but instead “Which of these areas fits the direction our business wishes to head in?”

What are the unmet needs in the area that your company is currently involved in? Ask if you are able to solve those problems with digital technology, and using that question as a starting point, take a good look at digital health.