Advancements in medical knowledge have led to increased complexity of care delivered by multiple teams often across organisations. As the population ages, delivering such care will become increasingly difficult. Real-time digital medicine, enabling patients to view their own medical records, which contain high quality information, and enable them to make choices about the care they receive affords the opportunity to empower patients and clinicians.

In the 1960s, a patient admitted into hospital with a suspected myocardial infarction would be in bed for six weeks. He was looked after and monitored by the concerned nurses. After six weeks, he would either be discharged all ‘cured’ or succumb whilst in his bed and die. No further follow up, tests and no medication was needed. What is the current scenario? Today, we are able to do ECGs, measure troponin T levels, arrange coronary angiograms and perform primary angioplasty or provide thrombolysis. In the immediate post-myocardial infraction period, we can closely monitor patients’ every passing second, beat by beat monitoring for cardiac arrhythmias and institute treatment appropriate to the patient’s needs and even adjusted to the patient’s own physiological parameters. Patients are assessed for hypercholesterolaemia and diabetic status and further ongoing treatment is provided. They are put through a cardiac rehabilitation programme which then continues for the rest of their lives. A great deal of effort is now being placed on trying to identify people at risk of heart disease and even on preventing it by targeting children and young adults to improve their lifestyle. As populations age and more and more elderly people continue to live with ever increasing chronic disease, the complexity of healthcare as well as the cost of treating and maintaining them rises. It is envisaged that by 2050, the number of people needing care will rise to four times of what it is today. Already we have more people over age of 65 than those aged below 18 in the UK, indicating that there will be more and more people who will need to be looked after by ever fewer people who are at work.

How good is the information that patients and the public have today?

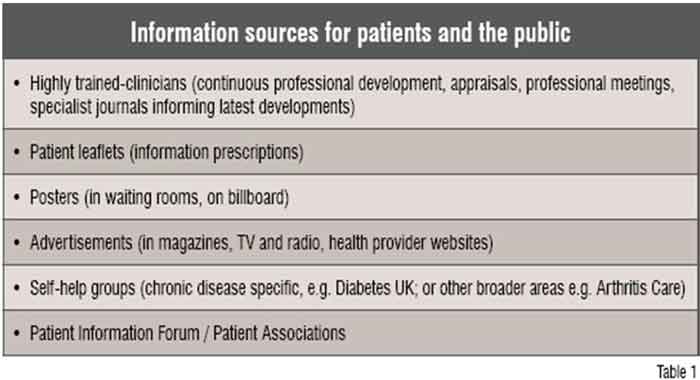

The advancement of medical knowledge has accompanied a plethora of information to help the patient and the public gain a better understanding of what is available and what can be done. (See Table 1)

There is ample information available to patients about anything they want, whenever they need it. The advent of the Internet has made searching for information even easier. But there are doubts regarding the authenticity of the information provided by it.

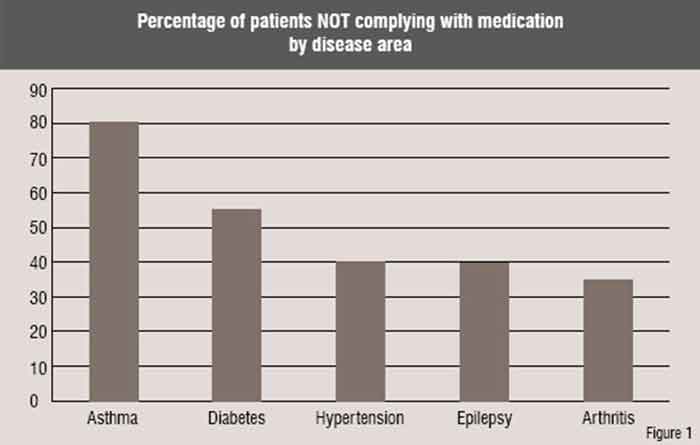

Compliance is poor even for conditions such as arthritis (see Figure 1) suggesting that the system at the moment is not meeting the needs of patients and a need for a new approach.

Creating knowledge-based healthcare systems

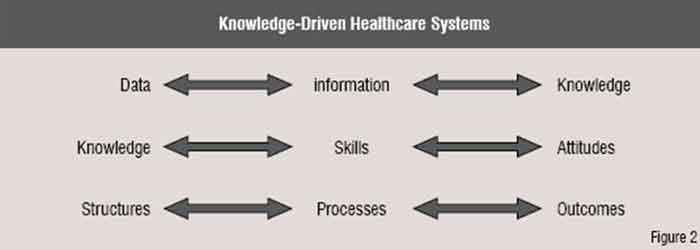

We now have the ability to economically check patient’s blood pressures (data) with sphygmomanometers that are available in the market. If patients browse high quality websites which inform them about blood pressure (information), they can monitor their own blood pressure and identify high and low blood pressure (knowledge). But to do this safely, patients should be taught certain skills (how to check blood pressure, what size cuff to use, use a machine that has been validated for this purpose and is regularly serviced and calibrated etc.) and certain attitudes (e.g. being aware of what needs to be done in case of high blood pressure). People should also learn where to check their blood pressure (e.g. provider institution, pharmacy, doctor’s waiting room, home). Once identified as having hypertension, they should be treated according to certain guidelines / protocols (processes) to achieve a specific outcome (reduction in risk of death, myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident). Healthcare systems have tended to focus on doing things without encouraging patients to think through why and what the consequences might be if these things do not happen. Hence, patients have not truly understood the implications of not following the advice given to them by their clinicians.

Clinicians can let patients see their health information but not abdicate their responsibility for providing care. Those patients that are able to look after themselves should be enabled to do so. But clinicians should also be aware of the patients who are unable to manage themselves well and who need their help and support. Multiple IT systems operating in different healthcare organisations or departments should be made interoperable to pull together data to display the information required for both patient and clinician wherever necessary. As people travel increasingly around the world, SNOMED-CT may become the common language to share such data in a semantic interoperable way so that data (such as blood pressure) can be displayed on the local clinical system. Such knowledge, skills and attitudes will be necessary for both clinicians and the patient to understand. This will lead to a certain type of practice and experience which can then also be measured e.g. through surveys or recording patient journeys.

In a knowledge-based healthcare system, a patient or citizen may think about checking their blood pressure and begin to understand how to reduce their risk of death by understanding how to monitor and control their blood pressure. (Data leads to knowledge). Conversely they may think about reducing their risk of death and realise that they need to check their blood pressure and then find out how to control their blood pressure as a result (Knowledge leads to what data to collect). This leads to a better understanding of the care they are receiving or what choices they can make to ensure good health or even encourage providers to meet their needs instead of just providing a service.

But do people care about finding out about their health?

According to comScore in August 2007, there were 37 billion health searches on Google and 8.5 billion on Yahoo. Online Health Search 2006 found 80 per cent of American Internet users, or some 113 million adults, have searched for information on at least one of seventeen health topics. Forty-eight per cent of heath seekers searched on information for somebody else. Thirty-six per cent of health seekers claimed their last search was for their own health needs. Fifty-three per cent of health seekers felt the information they had found an impact on themselves or how they cared for themselves. Whilst 74 per cent felt reassured that they could make healthcare decisions, 25 per cent felt overwhelmed by the amount of information they saw. Small groups felt frustrated by the lack of information, confused by the information or frightened by the serious or graphic nature of what they found online.

People are searching the Internet to understand their health-related problems. But the quantity of information is enormous. A search on Google for myocardial infarction reveals over 5.6 million results. The quality of information is variable and clearly not everybody has time to appraise the information whilst they need to make decisions on how to care for themselves or their patient. Even if people know that they should learn about their health, it is not clear where they should go, why they should go and how it will help them get better care.

Towards a partnership of trust

Whilst the clinician may be an ‘expert’ in what modern day medicine has to offer and what is available locally to the patient population, the patient is an ‘expert’ in how the disease is affecting him or her or what they might be at risk of, e.g. family history of conditions, environmental factors or personal behaviours that put them at increased risk of developing certain conditions. The mutual trust and shared understanding between patient and clinician will help in forming a Partnership of Trust. It helps in formulating the future plan of the treatment and also improves compliance from the patient.

Ensuring better outcomes

Patients need to know what conditions they suffer from, e.g. myocardial infarction or hypertension. These are terms that will be stored in their health record. Giving patients access to their own health records is the fundamental key to a better unified understanding between patient and clinician. If this is contained in an electronic health record, then the information can be instantly shared with the patient as well as the clinician as and when the need arises (Real time Digital Medicine). The patient can confirm the accuracy of the record (past history, medication, allergies as well as go over consultations, results of tests and the plan of action including next steps that have been jointly agreed as well as reviewing any other communication from other clinicians or healthcare providers).

These terms in the record, e.g. myocardial infarction, can then be linked to high quality information that the service provider has vouched for. An example that has the support of the World Health Organization (WHO) is the Map of Medicine . It is an evidence-based knowledge management tool that can be localised for particular geographical areas It is being deployed around the world and is available for patients in the UK at present. Patient data can be linked with information from the Map of Medicine as well as other trusted websites to develop knowledge. That knowledge should enable the patient to improve their compliance with treatment and the agreed shared plan.

Role of the service provider

During consultations, the clinician can record the shared plan of action, what has been agreed by the patient and the clinician and what should happen if problems are encountered or a change is needed. The patient may even be able to add their own comments as well so that a shared record is formed. This builds transparency into the Partnership of Trust and enables the patient and clinician to know what to do. As it is in the record and the patient can view it, the patient can also choose to share it with others who may also help (e.g. other clinicians, allied health professionals) or others whom the patient trusts, (e.g. carers).

Enabling access

The first step is to recognise the problem and gain a better understanding of the issues. The second step is to recognise that a solution does exist that allows patients and the public to access their health records online. Here in the UK over 40 GP practices are now offering the service. Almost 60 per cent of GP practices have been enabled to offer the service to their patients. We are currently developing guidelines for patients and clinicians on how to share health records safely with patients for clinicians and system suppliers. These could in future be adapted to a world-wide audience. In my own practice, over 400 patients are now accessing their own GP records. We ask everybody ‘Are you eMPOWERed yet?’ (The bottom-up approach of www.htmc.co.uk, see attached poster). The third step is to raise the issue at the WHO. The International Council for Medical & Care Compunetics is presenting a paper to the WHO on patient access to electronic health records . Raise this issue with your member healthcare organisations (the top-down approach).

Enabling patients to access their own health information can lead to a patient-centred healthcare system that does not provide tokenistic information but rather patient-specific information that is fit for purpose and could lead to better and healthier outcomes for an organisation as well as the individual concerned.

AUTHOR BIO

Amir Hannan is a full-time General Practitioner in Hyde, England. He is the Primary Care IT Lead for North-West Strategic Health Authority and is on the HealthSpace Reference Panel and the National Clinical Reference Panel for the Summary Care Record at NHS Connecting for Health.