Patients with atrial fibrillation and high bleeding risk (i.e., very elderly, acute stroke, renal/liver impairment or thrombocytopenia) represent an expanding group of patients who are still not getting the correct decisions regarding proper anticoagulation management plan despite the great benefit derived from oral anticoagulants. Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants could represent a new platform for easier handling and better anticoagulation strategy for this high risk group of patients with atrial fibrillation.

Non-Valvular Atrial fibrillation (NVAF) is known to be the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia worldwide and is recognised to increase the risk of major ischemic stroke by fivefold. Oral anticoagulants are used to reduce this risk. For several decades, Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs) were the mainstay oral anticoagulants. In the last ten years, however, the introduction of non-vitamin K antagonists anticoagulants (NOACs) has revolutionised the anticoagulation therapy for NVAF. The NOACs outperformed VKAs and showed several important advantages like the improved benefit-risk ratio with less intracranial bleeding, more predictable effects without the need for routine monitoring, andfewer food and drug interactions compared with VKAs. Today, there are 4 NOACs approved and could be prescribed: apixaban, edoxaban and rivaroxaban (i.e., the factor Xa inhibitors) and dabigatran. (i.e., thrombin inhibitor).

The clinical advantages of NOACs were confirmed many times in large randomised double blind clinical trials and in real world research studies. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines have clearly expressed a preference for NOACs over VKAs for stroke prevention in NVAF patients, especially if newly initiated (Class I, level of evidence A). However, in some countries, NOAC therapy can only be prescribed (and/or are reimbursed) if the international normalised ratio (INR) control with VKAs has been shown to be suboptimal after a failed trial of VKAs (i.e., 3-6 months of VKAs). This strategy might be risky for many patients due to the expected instability of pro-thrombin time and INR control during the first few months of VKAs initiation. Thus, in accordance with current ESC guidelines NOACs (when available or affordable) need to be considered as the first choice anticoagulation for NVAF. Increasing awareness of guideline recommendations regarding anticoagulation of NVAF patients might not be a difficult target. However, dealing with NVAF patients who have high bleeding risk still represents a great challenge to anticoagulation in daily practice.

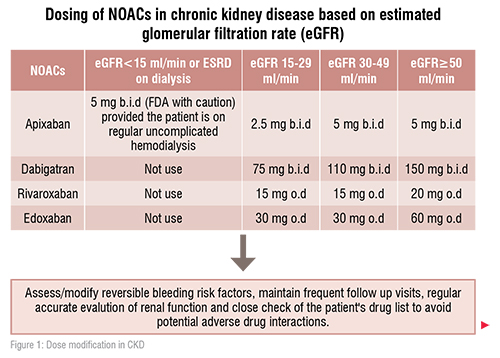

Renal impairment and NVAF are closely related and the number of patients with both conditions is increasing. Patients with NVAF and chronic kidney disease (CKD) have an increased morbidity and mortality due to their excessive risk for both thromboembolic and severe bleeding events that could make risk stratification and treatment challenging. All four NOACs are at least partly eliminated by the kidneys. Cardiologists should know the renal elimination rate of the different NOACs. Dabigatran has the greatest extent of renal elimination (80 per cent), whereas edoxaban, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, cleared 50 per cent, 35 per cent, and 27 per cent respectively, via the kidneys as unchanged drug. The available NOACs showed consistent efficacy and safety in patients with mild to moderate CKD compared with non-CKD patients in the respective subgroup analyses of the major NOAC trials. In patients with reduced glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) values, apixaban compared with warfar in was associated with significant reduction of bleeding event, and the stroke benefit reduction is maintained.[1,2]

When dealing with NVAF patients who have renal dysfunction:

Accurate evaluation of renal function is of utmost importance toward the best management strategy of cardiac patients. Before initiating NOACs, Cardiologists should estimate properly the renal function status/eGFR of the patient and follow the dose reduction algorithm for those with renal dysfunction.

Currently, no NOACs drug is recommended in patients with stage 5CKD (i.e. eGFR of less than 15 mL/min). Rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban (but not dabigatran) are approved in Europe for the use in patients with stage 4 CKD (i.e. eGFR of 15–29mL/min) with the reduced dose regimen. With the dose reduction protocol, the use of either apixaban or edoxaban may be preferable in these patients. Apixaban is (27 per cent) renally cleared, and the dose is reduced by 50 per cent according to its doser eduction protocol which is2× 2.5mg daily for patients with stage 4 CKD. Edoxaban is 50 per cent renally cleared, but its dose reduction to 50 per cent is applied to be 1× 30mg daily in stage 4 CKD. Rivaroxaban has an intermediate renal clearance (35 per cent), and its dose is reduced in stage 4 CKD by 25 per cent to be 1× 15mg daily.[1,2]

The role of NOACs in patients with end-stage renal dysfunction and on dialysis is unclear and subject to ongoing studies. The routine use of NOACs in patient with severe renal dysfunction (eGFR<15mL/min) as well as in patients on dialysis is best to be avoided. Also due to the lack of strong evidence for VKAs in this patient population (i.e. eGFR<15mL/min), the decision to oral anticoagulation should be very individualised, requiring a multidisciplinary approach and with respect to patients’ preferences.

There are no data on the use of NOACs in NVAF patients after kidney transplantation. If NOACs are to be used in patients with NVAF after kidney transplantation, the dosing regimen should be selected according to the estimated eGFR, and caution should be applied to the possible drug–drug interactions between the NOACs and concomitant immunosuppressive drugs.

The frequency of renal function monitoring depends on the stability of renal function. The monitoring interval (in months) can be calculated by dividing the eGFR (in ml/min) by 10; e.g.: if the eGFR is 50ml/min, 50/10= 5, therefore, the renal function should be monitored at least every 5 months, unless there were events potentially leading to an acute worsening of kidney function.

There is lack of randomised trials directed to investigate NOACs in very elderly with moderate renal impairment. However, there are specific recommendations for dose reduction of dabigatran and apixaban in NVAF patients ≥80 years, but not for rivaroxaban and edoxaban.

Very elderly patients usually present with several co-morbidities and/or are on multiple pharma cotherapies. This reflects the need for closer follow up and implementations of particular measures. Frequent checks of the patient's list of medications to look for the possible adverse drug interactions are important and might be lifesaving for the elderly on NOACs.

Patients ≥80 years who receive NOACs should be monitored more closely (i.e., to evaluate their blood counts and liver/renal function at least every 6 months).

The use of oral anticoagulation in this group of very elderly patients must be decided on an individual basis. However, when assessing the net benefit for an individual patient, the higher risk of thromboembolic events should also be taken into account. Several NOAC labels include specific instructions for dose reductions for patients ≥80 years. For dabigatran, dosage should be reduced to 2× 110mg daily, if patients are ≥80 years. For NVAF, the apixaban dose should be reduced to 2× 2.5mg in patients ≥80 years, if one of the following two other criteria is met: body weight≤60kg or serum creatine ≥1.5mg/dl. For rivaroxaban and edoxaban, no dose adjustment is recommended for patients ≥80 years.[1,2]

Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia could mandate precautions or even contraindications to anticoagulation. With increasing prevalence of viral illnesses, liver disease, cancers, use of complex pharmacotherapy regimes, etc., finding various degrees of thrombocytopenia is not uncommon in daily practice.

Studies on anticoagulation in NVAF patients with thrombocytopenia arescarce. Patients with high thromboembolic risk and a platelet count of >50,000 per mm3 is considered appropriate for therapeutic oral anticoagulation. This cut-off has also been used in recent studies. Full-dose anticoagulant treatment is usually considered unsafe for platelets <50,000per mm3. Those patients with platelet counts between 20,000 and 50,000 per mm3anticoagulation may be considered only in very specific situations on a case-by-case basis and prefer ablyprophylactic doses of heparins (i.e., 50 per cent of the therapeutic dose) should be used for those with high risk of ischemic stroke. In patients with platelet count of less than 20,000 per mm3, anticoagulation is contraindicated.[1,2]

Patients with thrombocytopenia need frequent follow up of their platelets counts and coagulation profile.

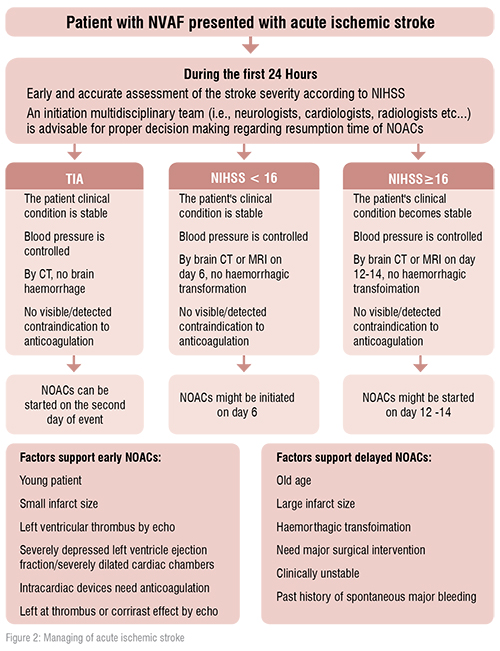

In the real world practice, a major challenge remains regarding how long does the interval between acute stroke and restart of NOACs in NVAF patients? This question continues to be unasnwered as patients with acute/recent stroke were excluded from the NOACs trials. Acute stroke in atrial fibrillation patients is associated with high rates of ischemic recurrence during the first 90 days.

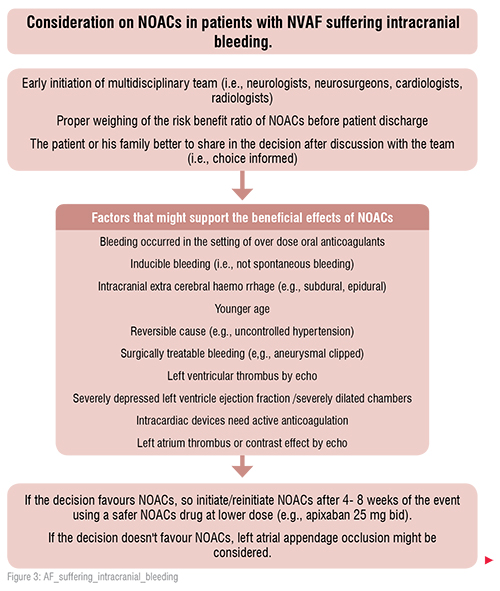

After a transient ischemic attack, if there is no bleeding and no ischemic lesion in the computed tomography of the brain, anticoagulation may be started immediately. After an acute stroke, if bleeding is excluded, and the score of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) does not exceed16, oral anticoagulation can be initiated on day four. In more severe cases (NIHSS> 16), anticoagulation must be initiated after at least two weeks. In patients who develop intracranial bleeding during oral anticoagulation with NOACs, anticoagulation has to be stopped immediately. Many factors have to be taken into account in order to decide whether or not oral anticoagulation can be resumed after4–8 weeks. If intracranial bleeding on NOACs occurs pontaneously ( i.e. there are no further precipitating factors, like uncontrolled hypertension or trauma) there is a clear contraindication to resume NOACs after the bleeding event. In this case, occlusion of the left atrial appendage is a preferred therapeutic option. [1,2]

In the setting of intracranial bleeding, the application of a shorter time period to resume NOACs may only be considered in life-threatening situations and compelling indications, such as symptomatic intra-cardiac thrombus formation or acute pulmonary embolism, and only after confirmation of haematoma stability by control imaging and strict blood pressure control.

The old belief that patients with liver disease are ‘auto-anticoagulated’ and are largely protected from thrombotic events has not been substantially assured by clinical data. The prevalence of liver disease is expected to increase with increasing prevalence of obesity, elderly, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, alcoholics, patients on multi-pharmacotherapies and autoimmune disease. Liver disease showed to increase risk of both bleeding and thrombosis.

Before initiating NOACs, liver tests and INR should be evaluated. All NOACs are contraindicated in patients with hepatic disease associated with coagulopathy and clinically relevant bleeding risk including Child-Turcotte-Pugh C cirrhosis. Rivaroxaban should alsonot be used in AF patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh B liver cirrhosis due to the risk of more than two-fold increase in drug exposure. Dabigatran, apixaban and edoxaban may be used with caution in patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh A and B cirrhosis. Careful attention should be paid to those with chronic liver disease, like chronic viral hepatitis and chronic autoimmune hepatitis who need closer follow up and precautions regarding adverse drug-drug interactions between NOACs and anti-viral or immunosuppressant drugs. [1,2].

Recognising patients at high risk of major variceal bleeding is of utmost importance before initiating NOACs. So, early collaboration among cardiologists, gastroenterologists/haepatologists, and haematologists may help optimising the use of NOACs in patients with liver disease, who simultaneously face high risks of bleeding and thrombosis.

Bleeding reduction strategy should be taken when it is necessary to prescribe NOAC to a patient with liver disease. This strategy should: measure baseline liver function tests, renal function, complete blood count, prothrombin time/INR, activated partial thromboplastin time, and screen for high-risk varices in cirrhosis for accurate estimate of bleeding risk;initiate proton-pump inhibitor therapy (especially if peptic ulcer disease), test for and eradicate Helicobacter pylori (as appropriate), provide alcohol cessation counselling; and minimise concomitant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antiplatelet use to reduce the incidence of bleeding event in such patients.

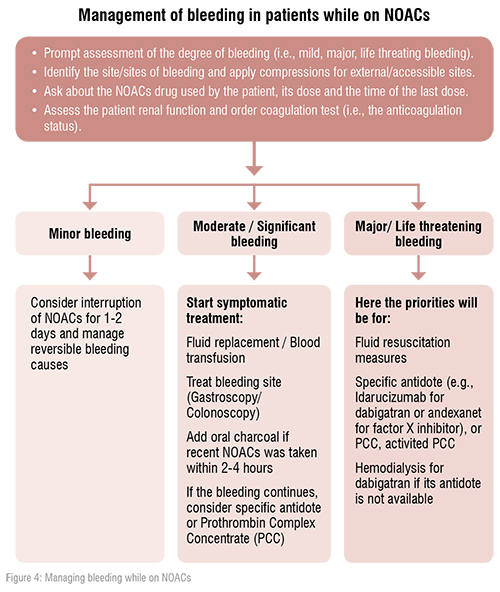

In the era of NOACs, cardiologists should have good knowledge along with updated strategies to reverse the NOACs’ effects in acute bleeding situations. This knowledge could be life saving for many patients presented with acute life threatening bleeding event while on NOACs.

An antagonist for dabigatran, idarucizumab, is available and recommended. An antagonist for factor Xa inhibitors (i.e., apixaban, edoxaban and rivaroxaban) andexanet alpha, has only been approved for clinical use in patients in the USA. Therefore, prothrombin complex concentrates are still recommended for the reversal of factor Xa inhibitors in case of lifethreatening bleeding in Europe. [1,2]

References:

1.Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, et al. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(16):1330-1393.

2.Gremmel T, NiessnerA, Domanovits H. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with an increased risk of bleeding. Wien KlinWochenschr. 2018;130:722–734.