Regulation vs. Innovation

Are we getting it right?

There is nothing new about the decades-old conflict between regulation and innovation. By definition, innovation is new and uncertain, and therefore risky, while regulation implies control, as in control of the risk from new, untried products. Nonetheless, have we now reached the point where controlling technology has become more risky than allowing promising innovations into the medical marketplace where they can be field-tested while providing access to patients willing to accept the risk. This has been the dilemma that regulatory agencies have struggled to address by ratcheting up their expedited review and approval programs, efforts that will remain half-measures without rapid retooling of the evidence base utilised for regulatory decision-making.

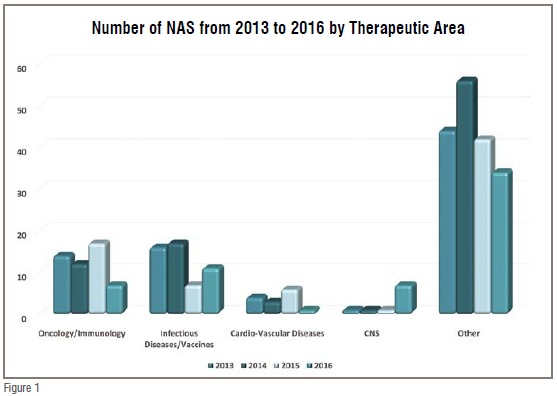

Although prescription drugs comprise a relatively small percentage of overall healthcare expenditures, they nonetheless represent the primary point-of-contact between the majority of the population and the healthcare system. While 62 per cent of Americans fill a prescription in any given year, only 8 per cent typically experience a hospital stay. Worldwide the percentage of healthcare expenditures on medicines ranges from 5-10 per cent in most developed countries to as much as 60 per cent in many developing countries. Thus, in an era when healthcare systems worldwide are confronting the dual challenge of cost-containment and the critical need for breakthrough treatments a primary concern for decision-makers is how well our system is meeting the medical needs of the population, and the role played by prescription drugs. These challenges are increasing in scope and complexity as the world confronts what the World Health Organization (WHO) refers to as the double burden of disease – the current crisis with epidemics, even pandemics, of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, along with the growing contribution to mortality and morbidity from Non-Communicable Disease (NCD). A 2015 McKinsey report notes that in Southeast Asia alone, they will experience a 29 per cent increase in the contribution of NCDs to all-cause mortality by 2030 compared to 2005. At the same time, current expenditures on public health are approximately 4-5 per cent of GDP in China and India, compared to twice that in most western European countries. A related trend adding to these challenges evident when looking at the worldwide output of New Active Substances (NASs are the first approvals of novel drugs anywhere in the world) over the last four years (2013-2016), is that just two therapeutic areas have dominated the last few years (see Figure 1 below).

Oncology has become dominant over the last decade with cardiovascular and CNS disease approvals falling far behind, while infectious disease/vaccines has reached parity with oncology just in the last few years. There are two over arching reasons to be concerned about this trend. The first is that the trend is not in sync with public healthcare needs. While cancer is certainly a major health problem, it is not the world’s number one health concern in terms of mortality and morbidity, while cardiovascular disease is the #1 killer in the US in terms of overall mortality with the potential to cause a substantial increase in premature deaths in many developed and emerging market countries in the near term. Nor is cancer the most urgent need in terms of innovation, as half of new cancer drugs are among the most novel of genomically-targeted precision medicines and cancer therapy is benefitting significantly from new advances in immunotherapy as well. The second reason for concern is that the trend runs counter to the mission of national regulatory authorities (NRAs). NRAs should be addressing unmet medical needs with time and effort proportionate to the public health impacts of the causative diseases within the limits of their resources. If this is not being done, then agency decision-making on priorities and resource allocations should be examined, and recalibrated if necessary.

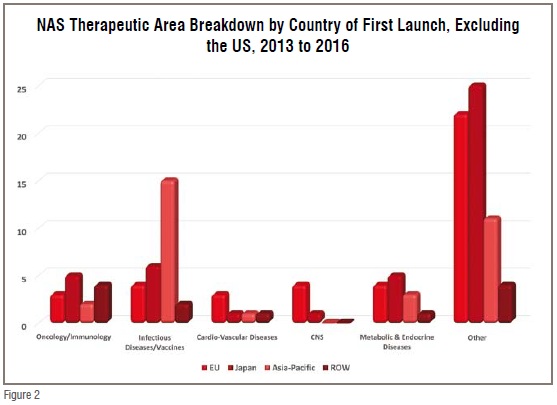

The NAS approval trend is, however, both troubling and perplexing in another context. While NRAs control how many and how fast products reach the marketplace, it is the pharmaceutical industry that controls what drug candidates enter the development pipeline. The two therapeutic areas that have remained static in recent decades – CNS and CVD – represent areas with substantial market potential. Mental health was tied with cancer as one of the four most costly conditions in the US during the decade of the 2000s, and the American Heart Association estimates that over 1/3 of Americans currently suffer some form of CVD. Worldwide CVD is considered the fastest growing NCD health threat as obesity becomes epidemic in developing countries with a growing penchant for adopting western diets that pre-dispose its adherents to metabolic syndrome and its disease sequelae. Meanwhile, WHO projects that by 2020, depression will be the second leading cause of disability worldwide. Despite the enormous market opportunity, however, the number of NAS approvals in these therapeutic areas have been static or declining, with both therapeutic areas together equaling less than half the number of oncology approvals from 2013 to 2016. At a time when there is increasing availability of prognostic and diagnostic technology for CNS disorders, and promising new approaches for CVD from regenerative medicine and drug-device combination therapy, the continued dominance of oncology/immunology, at 20 per cent of novel drug approvals and 47 per cent of the pipeline (according to a 2017 Pharma projects report) is both economically and medically out of balance. This “bunching up” of the pipeline with oncology products appears to some observers to be a waste of resources as there is now a surplus of competition in some relatively narrow cancer indications. Moreover, a SCRIP Pharma Intelligence analysis in mid-2016 demonstrated that immuno-oncology is one of the least successful therapeutic areas in terms of Phase III projects moving on to a regulatory filing at only 40 per cent success (compared to 58 per cent for all ~1500 products analysed). While it is true that the recent NAS dominance by oncology approvals is largely a US phenomenon (80 per cent of oncology approvals among global NASs were US) the fact that 50 per cent of NASs worldwide originate in the US and that nearly 50 per cent of the global pipeline is focused on oncology makes it a global challenge going forward, i.e., the non-US output of NASs appears to have a somewhat better balance of therapeutic areas (see Figure 2), but it is only half the story for the reasons just discussed.

The Up and Down Side of FRPs

Economic dictates of supply and demand, and what the market will bear, explain some of industry’s high level of interest in oncology drugs. Over the last 10 years, the average price for oncology treatments has risen sharply. While high prices act as a ‘pull’ incentive for oncology research and development (R&D) (i.e., they increase the likelihood of sufficient return on investment and thereby act as an R&D incentive), regulatory initiatives aimed at speeding development and review times serve as an equally powerful ‘push’ incentive (i.e., they lower the financial and logistical barriers, and reduce the risk of entering the field of research). Another reason for industry’s focus on oncology is that the enormous investment in basic research by the US National Institutes of Health has led to greater understanding of the pathophysiology and genetic mechanisms of many cancers, which provides exciting new and fertile areas for commercial product development. Also, the field of cancer research, over the years, has benefitted from a very effective patient advocacy movement. The American Cancer Society, for one, has been described as “the single most effective disease-based lobby in American pharmaceutical regulation.”

Advocacy is by no means a negative factor but it is a discriminating factor in how resources are prioritised in both the public and private sector. Forexample, the US FDA employs a full panoply of what the Center for Innovation in Regulatory Science (CIRS) calls Facilitated Regulatory Pathways (FRPs): priority reviews (receive a six month review time, compared to a 10-month standard review); accelerated approvals (conditional approval based on surrogate, or indirect measures of benefit); fast track designations (increased access to scientific interaction with the FDA and rolling reviews of portions of product application as they become ready); and breakthrough therapy designation – BTD (includes fast track incentives and ‘all hands on deck’ collaborative, cross-disciplinary engagement by FDA). In the 2000s, oncology drugs received 45 per cent of all FRPs awarded by the FDA. The relationship between regulatory initiatives designed to speed access to important new medicines, and industry’s focus on oncology is supported by the fact that if you look at the number of oncology approvals during the ten-year period before FRPs were implemented (1984 -1993), oncology was not even in the top five therapeutic areas for US approvals. Another example of the dramatic impact of advocacy and in turn the dramatic incentivisation effect of FRPs can be appreciated by the efforts of a stakeholder group of 50 healthcare and labour organisations who petitioned the US Congress to pay attention to the needs in the area of antibiotic resistance. The outcome was the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act, allowing expedited review and approval as well as 5 years market exclusivity, which a USG report in early 2017 stated was already responsible for 101 designations and 6 approvals less than 5 years into the programme.

While it’s not surprising that at a time when the out-of-pocket costs to develop a new medicine exceeds US$1 billion, many companies would be drawn to areas that receive favourable regulatory treatment. An analysis of drugs discontinued during development from 2001 to 2011 showed that financial and strategic factors were responsible for 56 per cent of the discontinuations. Regrettably, however, not every disease area can have its own GAIN Act. Political will and public advocacy are often lacking, and resources at regulatory agencies are finite. It is a zero sum game. The US FDA itself has pointed out such an imbalance can result in performance deficits in one area of responsibility to the detriment of another. This consequence has also been supported by the 2017 Pharmaprojects report highlighting that the expansion of the share of the pipeline by oncology was resulting in other therapeutic areas ‘being squeezed out.’

Emerging Sponsors are the Future

The new drug research and development paradigm is shifting rapidly from traditional big pharma to venture capital–backed small companies. An emerging sponsor is defined by the US FDA as the sponsor listed on the FDA approval letter who, at the time of approval, was not a holder of an approved application in the Orange Book or the regulatory management system for the biologics license application. Of new molecular entity/new biologics approvals in 2011-12, approximately 40 per cent were from emerging sponsors. Emerging sponsors share many of the same characteristics as companies referred to as start-ups, or small companies with little or no experience getting products into the marketplace. In early 2017, Pharmaproject reports that of approximately 4,000 pharma firms with active pipelines, 56 per cent have just one or two products in the pipeline, tacitly qualifying them as emerging sponsors. It also noted that Asian firms account for nearly 20 per cent of these firms worldwide, up from 16 per cent last year, and resulting not just from expansion in China but region-wide.

These emerging sponsors are critical to the future of innovation, particularly in challenging areas of R&D. For example, smaller companies have emerged to fill the void in R&D for CNS therapies. Similarly, they are often the seedbeds of innovative products and platforms in such critical areas of unmet medical need as orphan drugs. But, much of their pipeline is at an early stage of development and emerging sponsors come and go quickly. The dramatic demise of orphan drug sponsors has been chronicled in the literature on the ‘valley of death’ (i.e., surviving from late discovery through early clinical phase) but just how dramatic an impact was suggested by a Tufts CSDD study analysing the change in the number of orphan drug sponsors worldwide from 2007 to 2011, with the cohort losing ~150 companies that existed in 2007, but gaining ~200 new companies by 2011. The greatest change occurred among companies characterised as small pharma or small biotech, who experienced a considerably lower likelihood of remaining ‘in the game‘ throughout the period from 2007 to 2011, and yet these small companies comprised the lion's share of companies new to the orphan research and development enterprise by 2011.

Asia-Pacific Markets: Reaching Outward, Looking Inward

A McKinsey report in 2015 notes that Asia (arguably excluding Japan) has been one of the greatest beneficiaries of globalsation and is expected to have a CAGR of nearly 9 per cent from 2015-2020 in the global pharma market. Although manufacturing will remain an important contributor to growth in Asia, export-led economic models are now under pressure in most of the region. In China, exports as a percentage of GDP have declined from 37 per cent in 2006 to less than 20 per cent . In Indonesia, exports have dropped from 31 per cent of GDP to 19 per cent . One reason for the decline is that trade, whose contribution to global GDP grew from around 25 per cent in the 1960s to more than 60 per cent in 2008, has since stalled. Another is that Asia’s previously enormous manufacturing cost advantages have shrunk as wage growth has outpaced productivity. In the case of many goods produced in China for North American markets, for example, the cost advantage over manufacturing in the US has declined dramatically over the past decade. The spectre of rising protectionism, too, compels Asian policymakers and companies to ensure that they do not rely excessively on export manufacturing.

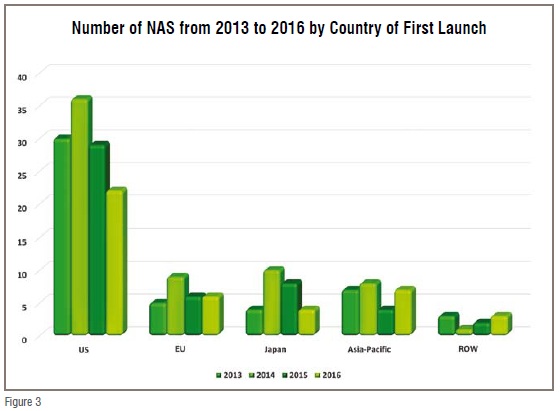

Nonetheless, the rising affluence of Asian households suggests that the region will continue to be the world’s biggest growth market for health care. China’s middle class is projected to expand by 36 million households and to represent 40 per cent of the country’s population by 2020, while another 20 per cent will be living in upper-middle-class and affluent households. Vietnam is projected to add 5 million upper-middle-class households by 2020, India 11 million, and Indonesia 29 million, according to BCG’s Center for Customer Insight. The region accounts for 40 per cent of world trade—and trade within the region is growing faster than anywhere else in the world. The Asia-Pacific region’s 4.5 billion people account for nearly 60 per cent of the world’s population, and includes many of the world’s fastest-growing economies, according to the 2017 BCG report How Asia Can Win in the new Global Era. The Asia-Pacific region seems poised to become a growth market for pharmaceutical as well, as seen in Figure 3, Japan by itself is equal to the NAS output of the EU, while together with the rest of the A-P region it is almost equal to half that of the US.

Taking What’s Best from East and West

What can the Asia-Pacific region due to improve its drug development output as well as to ensure that it is meeting its domestic medical needs while taking advantage of the dearth of needed medicines in other lucrative markets internationally.

Prioritisation – This must happen regionally. A national or regional commission of medical priorities should be convened and comprised of experts from government, academia, industry, patient advocates, and the medical establishment. Its responsibility would be to assess the country’s immediate and long-term health needs, and review the innovation landscape to determine whether current public and private R&D efforts are appropriately focused and funded. Another step would be to create an FRP Office within each NRA that would triage new drug applications guided by the commission recommendations. To help subsidise these activities, sponsors of candidate drugs would pay an application fee to the NRA. If the new Office determines that a drug candidate is eligible for one or more special regulatory programs, the sponsor would be exempt from paying any additional fees beyond normal user fees.

Patient Focused Drug Development (PFDD) – According to the US FDA, PFDD describes efforts to ensure that the review process benefits from a systematic approach to obtaining patient perspectives on disease severity and unmet medical need. As an example, in the field of CNS, the FDA has proposed a new approach for Alzheimer’s Disease that allows treatments of pre-symptomatic patients to slow the accumulation of substances in the body believed to be biomarkers of clinical disease, or to treat patients with early disease before functional impairment is apparent through an accelerated approval pathway on the basis of assessment of cognitive outcome alone. Although risky, there is precedent from AIDS activism in the 1990s, during which the FDA and industry handled the risks through patient involvement in a meaningful process of informed consent. Another example of a patient-focused approach was a George Washington University Stakeholder Panel publication of a report suggesting that obesity should be viewed as three conditions: obese but well, obese with risk factors, and obese and sick. Secondary end points for drug efficacy should be added on the benefits side of the scale, such as effects on joint pain, urinary incontinence, sleep apnea, and mobility.

New Technology – US FDA’s November 2015 report on its mission to keep up with advances in science states that among its main goals is the need to advance Regulatory Science (i.e., developing new tools, standards, and approaches to assess safety, efficacy, quality, and performance) in order to promote the lifecycle approach to regulation for both approvals and postmarket evaluation of risk-benefit profile of drugs, devices and biologics during their entire time on the market. The new FDA Commissioner has stated: “We need to close the evidence gap between the information we use to make FDA’s decisions and the evidence increasingly used by the medical community, payers, and by others charged with making healthcare decisions.” At the same time, the former FDA Commissioner said that he believes FDA needs to be proactive in breaking the logjam on the use of Real World Evidence (RWE) and digging more into “what patients care about,” while current CDER Director Janet Woodcock told the audience at a workshop on RWE that the current clinical trials system is broken and there needs to be new ways to collect and utilise patient data.

FRPs and Emerging Sponsors – There is a growing awareness that the regulatory environment has had a substantial impact on the introduction of innovative new medicines in certain therapeutic areas. It is likely that the use of FRPs is one reason why the US and Japan are more productive in terms of NAS output as CIRS reported in mid-2016 that approximately half of NASs approved in the US and Japan benefited from FRPs, but only 13 per cent of those approved by the EMA in 2014. We know that small companies are more likely to have multicycle review and less likely to garner approvals, with a 50 per cent approval rate as compared with 80 per cent for medium/large companies, according to an FDA study. It has also been shown in studies by the Tufts CSDD and others that FRP awards are important to investors, because they believe it is a harbinger of likely priority review status and flexibility on risk–benefit decisions by FDA.

Conclusion

There is nothing new about the decades-old conflict between regulation and innovation. By definition, innovation is new and uncertain, and therefore risky, while regulation implies control, as in control of the risk from new, untried products. Nonetheless, we have now reached the point where controlling technology has become more risky than allowing promising innovations into the medical marketplace where they can be field-tested while providing access to patients willing to accept the risk. This has been the dilemma that regulatory agencies have struggled to address by implementing facilitated regulatory pathways. These efforts, however, will remain half-measures without rapid retooling of the evidence base utilised for regulatory decision-making and proper attention to prioritising their application.

Acknowledgement: The author thanks Zachary Smith, research analyst at Tufts CSDD, for his contribution to the graphics and research on NASs.