The concepts for what the hospital of the future is likely to be and isnt include distributed services, the hospital at home project, wearable hospital telemedicine innovations, lean design principles and cellular care. These concepts dictate the design professionals responsibilities within an era of healthcare reform.

No administrator, patient or doctor today would recognise the hospital of the future. It isn't a healthcare facility, as we know it. As a result of changes in technology and the general delivery system, consolidation, amalgamation and an ever-changing regulatory environment, the hospital of the future will not be the resource-intensive and richly utilised organisation as it is today. Instead, the hospital of the future is likely to be smaller, less expensive to construct and operate, and sustainable in design, utilisation and energy efficiency. It will most likely be part of a distributed healthcare delivery system, rather than a stand-alone organisation. As part of the anticipated healthcare reform movement, hospitals of the future will be resource-appropriate and their utilisation rates will be proportionate and relative to their demographics.

As renowned author Regina Herzlinger points out in her 2007 book, Who Killed Healthcare, 'The US healthcare system is in the midst of a ferocious war. The prize is unimaginably huge-US$ 2 trillion, about the size of the economy of China-and the outcome will affect the health and welfare of hundreds of millions of people. Four armies are battling to gain control: the health insurers, hospitals, government and doctors. Yet you and I, the people who use the healthcare system and who pay for all of it, are not even combatants. And the doctors, the group whose interests are most closely aligned with our welfare, are losing the war.'

Architects contribute to the solutions

Do design professionals have responsibilities within this era of reform? Most certainly. In the recent past, healthcare architects and hospital planners have focussed on the issue of universal access and the implications of that on utilisation and hence, building size. The larger problem confronting this society now and well into the future is cost. In the healthcare field, cost drivers are multi-faceted and generally include most or all of the following:

Labour and Benefits

Architects can and should take an active role in the discussion about the kind of facility the hospital of the future would be. They could do it by:

Hospital utilisation trends

Another way for hospital architects to expand their sphere of influence is to understand and educate clients about key utilisation trends. Hospital resource utilisation results from both access and availability. Information from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care showed that the amount of time patients spent in a hospital varied greatly depending on where they lived and practice patterns of the local physician community. For instance, the patients who were chronically ill in Bend, Oregon spent only 10.6 days per year in the hospital, while those in Manhattan spent 34.9 days annually.

Additionally, the Dartmouth study illustrates that physicians adapt their practice styles to the resources available to them, which can cause huge variations in healthcare costs. Medicare spending for chronically ill patients at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota was only US$ 34,372 per patient, but that figure rose to US$ 64,900 at the University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center. This is because utilisation rates and physician visits were markedly higher at UCLA than at the Mayo Clinic (11.6 ICU days vs. 4.2 ICU days and 53 physician visits per stay vs. 24 visits per stay, respectively). In both these cases, enrollment in hospice care programmes was greater in Oregon and Minnesota than in Manhattan and Los Angeles, an obvious factor in the utilisation of hospital resources.

Current trends in hospital management and construction cannot be sustained by the US economy. Without comprehensive community planning, the boom in US hospital building is replacing many outmoded facilities and adding beds to respond to the perceived needs of an ageing population. This trend aggravates and sustains the utilisation and practice patterns identified in the Dartmouth study. Higher utilisation results in higher costs due to greater expenditure of resources such as energy, capital and supply chain materials.

Impact of healthcare policies

We all recognise the influence of policies and policymakers on the design of healthcare facilities, including the need for eight-foot corridors, one-hour fire safe corridors in nursing units, and accessible design that provides safe ergonomics for disabled and non-disabled staff alike. But these are just a few of the reasons that the hospital of today got to where it is. To fully appreciate the current state, one only has to reflect on legislation such as the Hospital Survey and Construction Act (also known as the Hill-Burton Act) of 1946 that provided federal grants and guaranteed loans to improve the nation's hospital system and help to achieve a goal of 4.5 beds per 1,000 in population. These grants did not sunset until 1975 and every hospital in the country had benefited from this funding source.

Before Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO's) began providing insurance coverage, there was indemnity insurance-hospitals were paid what it 'cost' to provide care. Length of stay was not an issue and patients were routinely admitted to a hospital bed the day prior to a surgical procedure to complete their pre-surgical lab work and imaging. There were of course, Health Systems Agencies (established in 1975) to provide local direction and control of healthcare planning. The local agencies developed health systems plans that mandated the number of beds, operating rooms, ED stations and so on for each planning area. Some would argue that their effect was limited in terms of curbing and controlling growth. Certificates of Need (CONs) were created in 1974 to help control how hospitals spent their money; capital expenditure was limited and expansion plans had to fit into the local Health System Area (HSA) plans. Most states that had CONs have let them sunset because they, too, generally failed to meet their intended aim of reducing spending and expansion of services. These and other regulations helped to bring about the current state of the healthcare delivery system.

Realising the hospital of the future through design

Hospital designers need to join the 'ferocious war' described by Harvard economist, Herzlinger. Designers can advocate for changes in their clients' practices, push for smaller concentrations of healthcare resources and urge client groups to disperse their services to be more accessible throughout the community. Using their influence to educate policymakers and benefit consumers, designers may assist in making many of the following concepts a reality.

The Advisory Board Company, an industry based think-tank in Washington, DC, proposed that because of the uncertain regulatory and reimbursement scenarios ahead, the hospital of the future will specialise in key services. This new organisational structure may result in lifting of the moratorium on physician-owned hospitals and slowing the growth of stand-alone comprehensive healthcare facilities. Instead, it will encourage the growth of 'Centres of Excellence' that can deliver patient care within existing facilities, dispersed throughout a community without the need to construct new buildings. Other futuristic healthcare delivery options include:

Lean design

Architecture is central to the discussion of 'lean design' for the hospital of the future. It literally can remove the walls in a healthcare setting that cause silos between staff and fragmentation of care delivery. By designing patient units that allow for single bed service line adaptable environments, architects can facilitate the achievement of measurable milestone outcomes, create opportunities for care providers to work differently (in multidisciplinary care teams) and minimise patient movement.

The 'five big ideas of lean' outlined here can be embedded into healthcare design and project delivery to remove waste in the capital programme:

1. Collaborate, really collaborate

2. Increase the connections of the participants

3. Develop a network of commitments

4. Optimise the whole and not the pieces / departments

5. Couple learning with action

Planning for optimised patient care delivery offers a multitude of operational benefits, such as the reduction of steps and cycle times, elimination of patient handoffs, enhancement of the predictability of workflow and commitment to the 'lean' process, reduction of staffing requirements and improved quality of patient outcomes. It also equates to less facility space required, fewer dedicated or specialised function spaces and the dissolution of departmental fragmentation.

Cellular care

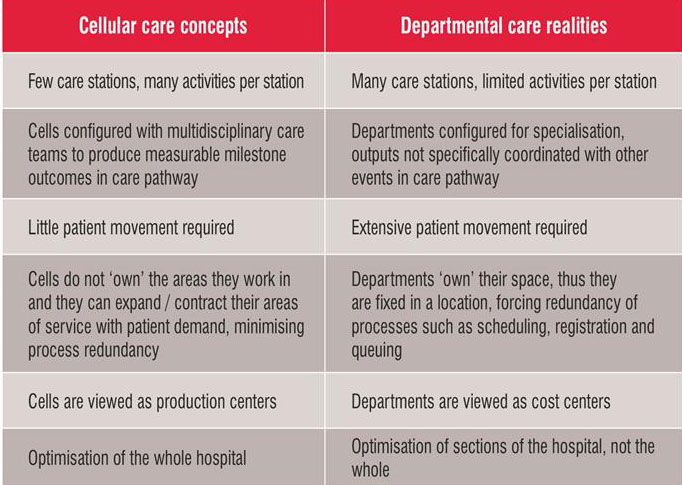

Cellular care (also known as multidisciplinary team care) is likely to be the operational model for the hospital of future. Table 1 illustrates the efficiencies and outcome improvements to be gained by this new paradigm in comparison to the current healthcare delivery model.

California's hospital of the future

Sutter Health, headquartered in Sacramento, California has embarked on a plan to implement and open prototype hospitals embodying the principles of lean design and cellular care. In order to break from the conundrums of current delivery methods, Sutter shared its models and objectives with multiple architectural teams. In the process, it split the design project delivery process into a competitive planning and pre-design stage followed by implementation by the 'winning' teams. As the owner, Sutter prioritised the drivers for each project and they are: patient safety, staffing efficiency, cost project adaptability and flexibility.

Project teams (including members from operations, programming and design and build firms) were assembled prior to proposing to participate in this collaborative process. Three teams were selected to compete for the opportunity to design Sutter Health's prototype hospital and each team was awarded US$ 500,000 to develop their proposals. In the kick-off meeting, all the three teams were involved in determining the project's metrics and actual delivery schedule.

The prototype hospital objectives were outlined as:

Sutter now has four prototype hospitals in design production and expects to bring them online within the next few years. They all appear to have met the objectives set out by the owner, and should be among the most cost-effective and efficient hospitals in the country upon completion.

Conclusion

Healthcare designers and planners have ample opportunities for thought leadership in this arena. The hospital of the future most likely will include distributed services, a hospital at home prototype, wearable hospital telemedicine innovations, 'lean design' principles and 'cellular care' concepts. Instead of focussing on what the hospital of the future 'isn't', architects.

AUTHOR BIO

Gary M Burk has been responsible for project and client management of healthcare facility planning projects, including utilisation analysis, facility assessment, space programming, user group interviews, planning standards development and master planning. He has more than four decades of professional experience, working as a practitioner in major architectural offices.

Terrie Kurrasch has an extensive background in facility planning and healthcare administration. She has worked exclusively within hospital and healthcare organisations, and as a healthcare management consultant. Terrie came to Ratcliff after managing the implementation of the merger of Alta Bates and Summit Medical Centers.