Reliability and safety are now essential components of healthcare. However, providing better care requires a proactive approach from the providers.

From a scientific point-of-view, healthcare has improved dramatically over the past 50 years. The development of new treatment modalities has had a significant impact on many people. This, of course, differs from country to country, as well as within countries and communities. Access to the standardised and reliable care that should be provided is often difficult to obtain. It is a truism that if we applied the knowledge we now possess, even without any new innovations, millions of people would be cured of the conditions that afflict them. The issue now is to improve the delivery of healthcare rather than the development of new treatment modalities. The urgent need is to move from quality assurance to quality improvement, to learn how to measure improvement and to develop systems that facilitate safety and reliable delivery of healthcare which inherently minimises risk.

In many countries, there has been a move to examine the delivery of healthcare in terms of quality and safety. The domains of quality, as delineated by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the USA, can be used as a framework to define the way we approach the provision of healthcare worldwide. Although these concepts of quality were developed in the most sophisticated of health systems, they are sufficiently simple to be applied to any system. The key factor is that quality places the needs of the patient at the centre of all that we do in healthcare. The emergence of evidence-based medicine over the past 20 years has focussed our attention on ensuring the effectiveness of healthcare, though there was no surety that this will happen every time. It is therefore necessary to reconsider the way we organise and deliver healthcare. The challenge is to deliver the correct care reliably all the time, according to patient needs.

What does reliable healthcare mean?

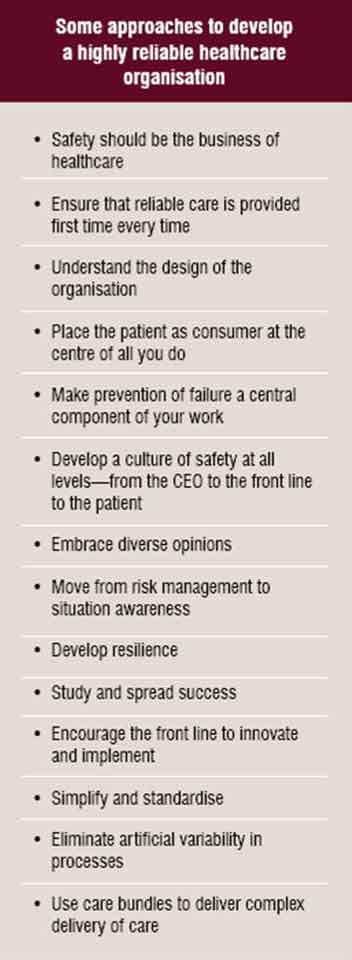

The science of reliability was developed in other industries and is now being adapted for use in healthcare. The examples of highly reliable organisations could be found in the field of nuclear power, railways and airlines. The key issue in highly reliable industries is the central belief that systems need to be in place to ensure the safety of consumers. It is the only reason for them to survive in their respective fields.

In essence, the patient should expect to receive the correct and effective care that is affordable every time he or she visits the doctor or nurse. Unfortunately, this is not the experience even in the most highly financed healthcare systems. The variability of healthcare provision is immense and as providers we need to redesign the systems in which we operate to approach an environment where the patient receives what they need every time. The concept of reliability requires some understanding of the need for safety. Safety is not inherent in the systems within which we work. In order to have a reliable system, one need to move from risk management and reaction to proactive situation awareness, this mitigates harm.

Reliability principles, which include evaluation and calculation of the overall consistency of a complex system, are effective tools used in other industries to improve both safety and the rate at which a system produces consistent quality outcomes. The challenge is to adapt this reliability methodology to the healthcare delivery system so as to ensure the safe delivery of healthcare.

From an abstract point-of-view, reliability is measured as the number of actions that achieve the intended result divided by the total number of actions taken over time. The concept of reliability in healthcare is defined in terms of the number of times the evidence-based care is not provided. Level One (10-1) reliability

results when there is a failure rate of one out of ten, i.e. we get it right at least 90 per cent of the time. The next level of reliability, Level Two (10-2) refers to a failure rate of one in a hundred. Nuclear power, which is at the sixth level, operates at a failure rate of less than one in million (10-6). Chaos exists when the failure rate is more than two out of ten attempts.

The provision of healthcare rarely reaches more than the first level of reliability. Most healthcare systems operate in the ‘chaotic’ zone without common articulated processes and many doctors and health professionals continue to work as individuals. Although it is essential, the common approaches of asking professionals to work harder, undertake more training and to follow guidelines do not produce more than the Level One reliability. To attain Level Two reliability, organisations need to recognise the impact of human factors on the delivery of safe healthcare. This implies the need to introduce checklists, memory aids, redundancy in processes, and defaults in decision-making. Level Three reliability requires a redesign of the system so that it focusses on

processes, structure and their relationship to outcomes.

How does one develop highly reliable healthcare delivery?

The first issue one needs to address is an understanding of the need to approach safety from a more proactive stance and to accept that the human factors that cause harm can be controlled if one designs a system that prevents harm in the first place. In our daily lives, we accept reliability in most of what we do; for example, how the trains run, how airlines view safety, food quality etc. We have often used the individual requirements of the patient to assume that it is not possible to apply some of the key principles required e.g. standardisation, routine, checklists. The problem in the past was that we expected hard work and good intentions to deliver reliable healthcare. Insisting that providers be more careful and vigilant simply has not worked.

Once safety becomes the method of operation, one moves to examine the system in which we work, viz. how we have designed the complex process in reaction to previous mistakes, or as a system that has placed safety in the forefront. For example:

• Do we have systems that prevent common errors from occurring?

• Do we define the way we want to deliver healthcare to ensure that the patient is protected from harm?

• Can we break down the problems into small bites so that the system can be addressed in a simple way?

Medication errors are a good example, which probably account for the maximum harm in hospitals. The aim could be to decrease the number of errors year on year, until zero error is achieved. This is a goal we have set at Great Ormond Street Hospital as we strive to achieve a transformational goal of Zero Harm. To reach this ambitious goal, the organisation is committed to develope a culture of not accepting the inevitability of harm but rather developing one that accepts its preventability. This requires a total redesign of the way we deliver healthcare; not merely addressing external targets.

Understanding and then eliminating the artificial variability—which is introduced by providers—and managing the natural variability brought by clinical need go a long way in ensuring consistency. The standardisation of healthcare without decreasing the individual requirements of the patient is a difficult task and will require an understanding.

The use of care bundles, the packages of evidence-based care to ensure that all elements are delivered, has helped to eliminate most of the common problems like line infections and medication errors in hospitals in Europe and North America. The WHO World Alliance for Patient Safety initiative introduced checklists to improve outcomes in surgical care. This is a key element in the move from Level One to Level Two reliability. This approach requires a rethink of how we deliver heathcare. We can no longer accept delivery by health professionals acting as individuals.

How does one bring this to a universal audience?

How does one bring this to a universal audience?

In reality, the concept of reliable healthcare should not be difficult to sell either to the consumer or the provider. The problem is that we have a preconceived notion that we are already delivering reliable care. The right approach must, therefore, include recognition that unless one accepts the inherent inconsistencies in the present healthcare system, one will not develop a coherent approach to safety. The theorists have tended to make the concepts inaccessible to the patient and to the healthcare provider. To address this problem, and to ensure that this is not a concept only applicable to wealthy economies, one needs to reinterpret the issues for the relevant audience, using examples from outside healthcare and then applying them to the local environment. For example, one can look to other organisations that have solved the problem, adapt the solution for local use, measure the outcome and then apply small tests of change.

Conclusion

The ideas of reliability can either excite or turn off healthcare providers. In order to make this an attractive option, one needs to reframe the debate for managers, clinicians and patients. Once the patient is in the centre of the debate, the argument becomes an essential component of solutions for healthcare. Demystification of this concept is essential. From a management point-of-view, ensuring that the patient gets the correct evidence-based treatment the first time every time, has a financial gain that will make most executives satisfied with the knowledge that the quality has been enhanced.

AUTHOR BIO

Peter Lachman is Consultant in Service Redesign and Transformation at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children and a consultant paediatrician at the Royal Free Hospital in London. He was a Health Foundation Improvement Fellow at the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in 2005-2006. He leads on the transformation programme at GOSH.