This article summarises the recent trend in healthcare design of using Lean-inspired rapid prototyping to develop, refine and evaluate clinical processes and space allocation very early in the design process. The article presents a brief description of the Lean philosophy, a description of the rapid prototyping process, steps to conducting a rapid prototyping event, typical outcomes of an event and, finally, recommendations for conducting a successful rapid prototyping event.

There is a new Lean-inspired trend in healthcare planning in which planners, design professionals, and care providers can be seen moving cardboard walls around in large warehouse-type spaces to simulate high-intensity healthcare areas such as the emergency department, surgical suite, oran imaging center. These groups are most likely participating in a rapid prototyping event designed to quickly test, communicate and evaluate operational and facility solutions.

To understand rapid prototyping, a Lean tool, it is important to have a basic understanding of the Lean philosophy. The term Lean refers to a management strategy that, simply, creates value by eliminating waste. Although the Lean management concept is most closely associated with Japanese manufacturing, particularly, the Toyota Productions System, it has been extensively applied to healthcare in the last decade. Experts estimate that 30 to 40 per cent of healthcare production is waste and rapid prototyping is one of the Lean tools that can assist organisations in streamlining operations and removing waste during the planning of a renovation or replacement project.

A rapid prototyping process is the opposite of the change process, common to healthcare, in which multiple discussions occur and, then, there is a prolonged review and approval process. Often, initial design decisions are made based on existing facilities or in essence, the status quo. Therefore, clinicians have limited input in the fundamental decisions related to how care is delivered. Rapid prototyping addresses both of these issues; it allows clinicians to rapidly test care delivery options and develop recommendations to improve the delivery of care.

The rapid prototyping process

The first step in the rapid prototyping process is determining if it is the right process. Rapid prototyping is expensive in terms of professional’s time, rental or acquisition of space, and participant’s amenities (e.g., transportation, food and drink, etc.). This article focuses on full-scale rapid prototyping, which is obviously more expensive than partial scale, or virtual prototyping. Therefore, careful thought must be given to how full-scale rapid prototyping is used. Typically, it may not be of much value for low intensity clinical or office space but it is very productive for high intensity, high cost departments such as surgery, the emergency department, obstetrics and imaging where careful study of operations can improve patient flow, reduce staffing costs and minimise space requirements.

Rapid prototyping events involve a cross-functional team, led by facilitators trained in Lean principles, who come together to solve a problem or improve a process. Participants do not need a detailed knowledge of all relevant clinical processes and, in fact, sometimes a limited knowledge of the processes will make a participant more open to questioning the status quo. Therefore, careful consideration must be given to participants. Suggested criteria includes knowledge of some component of the process, interest in improving the delivery of care, openness to change, and a willingness to commit the necessary time to the event. Facility planners, designers, and engineers may be included on the teams but must have an equal commitment to exploring new ideas.

In organising the event, the materials the teams work with should be:

Inexpensive: allows participants to tear apart and recreate solutions without concern for cost; typical materials for the event include cardboard, duct tape, markers and other similar materials

Quick: materials must allow participants to quickly test ideas, evaluate them, and, then, proceed to the next iteration; a large open space with a common shared area for materials works best

Minimal: utilising simple, minimal components will facilitate the thought process and rapid iterations; tables can be used for beds, boxes can be used for sinks, etc.

Testable: providing minimal but realistic materials will allow patients to lie in a simulated bed, use cardboard walls to understand the size of a room, or tape a box to the wall to determine the optimal height of a sink

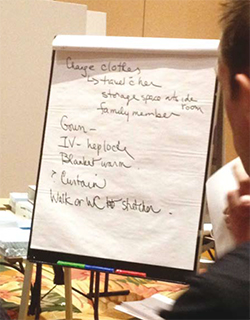

Measurable: quantifying findings is essential for participants must to document their recommendations (e.g., square footage of a room, location of equipment, etc.); therefore, participants will need tape measures, flip charts, cameras, or similar equipment.

The process, whether in a parking lot or in a warehouse, is similar. Typically, to initiate an event, participants meet as a group and are oriented to the rapid prototyping process and the goals of the particular event. It is important to emphasize to participants that a final finished room design is not the goal of the event. Rather, small incremental changes achieved through an iterative process (e.g. location of the stretcher, height of a charting station, solution to storage of patient belongings, etc.) are valuable findings.

Then, participants are directed to the rapid prototyping area where they will use cardboard walls and various pieces of real or simulated equipment to conduct small rapid experiments to determine the optimal processes and required organisation of the space. Typically, in facility-oriented rapid prototyping events, a clinician and facility planning professional are asked to lead each team. These individuals are oriented to the Lean philosophy and group facilitation techniques prior to the event.

Typically, teams are instructed to:

Observe processes and collect data, which can occur prior to the event or be gathered by simulating processes

Brainstorm opportunities to improve the process through discussion or, preferably, by acting out scenarios

Set goals for what the group would like to achieve (e.g. faster patient throughput, less movement of patients, fewer staff steps, etc.)

Start testing options quickly but making sure findings and results are recorded

Experiment and refine changes for the preferred approach

Standardise the process by testing it for different types of patients and situations

Present the findings to the other groups and document comments and suggestions

Celebrate success possibly with a snack break or photograph of the team and their solution.

Obviously, this approach will vary with the situation but, most importantly, the group should drive the prototyping process. At a recent rapid prototyping event, four groups of participants were asked to rapidly prototype a similar space. Each group approached the problem a little differently but there were many similarities:

After a 90-minute prototyping session, the groups came together and shared their findings, as well as, issues that remained unresolved. Although many of the findings were similar, many varied and there were several outstanding issues. All of the groups were eager to start a second session to further refine their solution and address the outstanding issues.

In the reporting sessions, some of the insightful comments made by group members were:

From a facility planning perspective, experience with this type of event has shown that prototyped rooms rarely significantly exceed the current typical size of a similar room or area. Without specific direction, but consistent with the Lean philosophy, most groups seek to minimise the space allocation and optimise the use of the space.

At the completion of a rapid prototyping event, the value of the event becomes clear: it is an effective way to engage clinicians and facility planners in developing specific operational and facility recommendations in a short timeframe. Participants often find the meaningful dialogue between clinicians and facility planners to be the most valuable take-away from the event.

Why rapid prototyping works

Rapid prototyping involves taking a group of clinicians and facility planners away from their work for a significant amount of time so many are cautious about utilising this process without understanding why it has received such positive reviews. The primary reason is that it leads to learning as defined by the Lean philosophy:

It is easy to see how rapid prototyping reflects these principles and results in a meaningful learning experience.

Integrating patients and families

Fortunately, patients and their families have not been forgotten in this process. Most organisations using rapid prototyping to find a way to integrate patient and family feedback into the process. Patient and family input may be incorporated:

At the beginning of the process

Patients and families may be invited to share their healthcare experience with the group prior to beginning the actual prototyping. In Lean terminology, asking patients and families to share their experience allows the customer to define value, which, in turn, will provide valuable input into the prototyping process.

During the process

Having patients and families participate in the prototyping process has been used but detailed staff discussions of processes may not be of interest to patients; therefore, there should be careful consideration of their time if this approach is used.

After the process

Patients and families may be invited to review the prototype and provide input. This is particularly appropriate if they have defined what they consider value and can see how it has been incorporated into the prototype.

Keys for conducting a successful rapid prototyping event

As one might imagine, considerable time and thought are required for organising a rapid prototyping event. Key recommendations for conducting a successful event include:

Invest in planning

Spend the necessary time to develop a detailed agenda, find the appropriate space, and assemble the needed materials. A well-organised and orchestrated event will show respect for the clinician’s and design professional’s time.

Pay attention to people

Invite the right people; participants that are interested, want to contribute, and are eager to learn. Because participants will be from many different disciplines, allow time for participants to introduce and sharing something about themselves during the orientation session. Team facilitators should make sure all members are participating and being heard.

Be hospitable

Most rapid prototyping events occur away form the workplace in a warehouse or large conference room so consideration should be given to the comfort needs of the participants such as transportation, food and drink, restrooms etc.

Provide feedback

Participants will want to feel that what they did and the time they invested mattered. Therefore, findings from the event should be documented and shared will all participants along with a note thanking them for their participation and time.

Start small

Given the complexity of a major rapid prototyping event, an organisation should consider starting with a small event to refine the processes and, then, gradually, expand the scope.

As the Lean philosophy has moved into healthcare arena, many of the Lean tools are being tailored for use in healthcare facility planning. Recently, a process for full-scale rapid prototyping of high intensity clinical areas has become a frequent tool in early facility planning. Although historically, mock-ups have been used to refine designs in healthcare, rapid prototyping is now being used in the early stages of planning as a tool to understand patient flow, streamline work processes, and optimise the space utilisation. And, early experience is showing that this Lean-driven learning process provides significant benefits to the facility planning process and has been enthusiastically received by clinicians and healthcare facility planning professionals. Looking toward the future, it is hoped that findings from these events will be shared so they can be used as a basis for on-going improvements in clinical processes and facility design.