The programming, planning and design of healthcare facilities are of prime importance to improve the patient, visitor and staff experience. In this article we will highlight 5 key design principles in the context of healthcare facilities with case studies.

The programming, planning and design of healthcare facilities is of prime importance to improve the patient, visitor and staff experience. The goal of architects, designers and medical planners is to envision design as good platform to innovate and create a welcoming environment for the users.

What are the ways to improve the health and vitality of the communities that are served by a healthcare facility? In this article 5 key design principles in the context of healthcare facilities with case studies will be highlighted to answer this question.

Designing greenfield hospitals particularly in urban areas often requires a careful and sensitive approach within limited land area and stringent development controls. It is imperative to maximise the site’s full potential without sacrificing on the quality of healthcare environment.

A case in point would be the Taikang Nanjing International Hospital (Figure 1), in Nanjing, China. The project is in an intensive topographical area outside of downtown Nanjing. The Gross Floor Area requirements coupled with the strict building height requirements (18 metres) required a low height building with a large footprint.

The impact of a large floor plate on a sloping site had to be addressed to minimise the cut and fill of the site. This drove the project to build into the landscape working as much with the existing contours as possible. This was unique for Chinese hospital developments as they typically are built on relatively flat surfaces with minimal grade change and posed several challenges with meeting China’s strict fire access requirements. This led to an open-air fire access path that ran the length of the building, which also doubled as a service access. In addition, it helped to reduce the volume of water runoff of the site during heavy rains.

The towers straddle the service / fire lane and connect to the roof of the diagnostic areas. This move allows the patient towers to have a very low scale with landscape on both sides (natural on one and the green roof on the other). Similarly, when arriving to the main entrance on the lower level it also only feels like a three-story building since the towers are very recessed — this created the level of intimacy, fitting the building into the landscape and maintaining a human scale with them as sing. The horizontal shades on the tower emphasise the fluidity and continuity with the landscape while also providing shade to the rooms within.

The right vision during the planning, design, and construction of a new healthcare facility can ensure a positive return on investment and lower the overall cost basis for ongoing operations. In order to minimise capital expense and ensure operating costs yield a suitable return on investment, facilities need to implement evidence-based design to lower the cost of care without compromising on quality.

In Parkway Health Gleneagles Shanghai International Hospital (Figure 2), Shanghai, capital expenses were saved by the creation of a central support services hub which was to be shared by several hospitals in the district. As a part of Shanghai’s New Hongqiao International Medical Center, the area’s shared services such as CSSD, laboratory and laundry are linked through its basement. To facilitate operational efficiency, the basement is also connected to the Imaging Center on the second floor.

The key to minimising capital costs is to envision an appropriate phasing strategy. For the hospital the right bed mix and facility planning helped in understanding the number and type of beds, operating theatres and clinics could be planned in first phase to generate maximum revenue. This helped testing out the right components and the subsequent phases were then planned in an incremental fashion. A holistic sustainability framework helped in cutting down operational costs and helped in creating a smaller carbon footprint. Some of these features do not involve additional costs — like day lighting and appropriate building orientation to minimise heat gain and maximise natural light, thus cutting long term electricity and air-conditioning costs.

Emergency Department Design

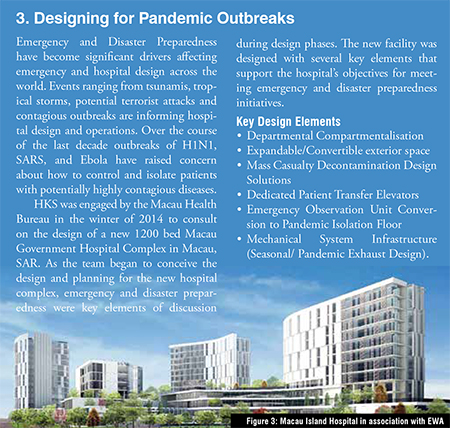

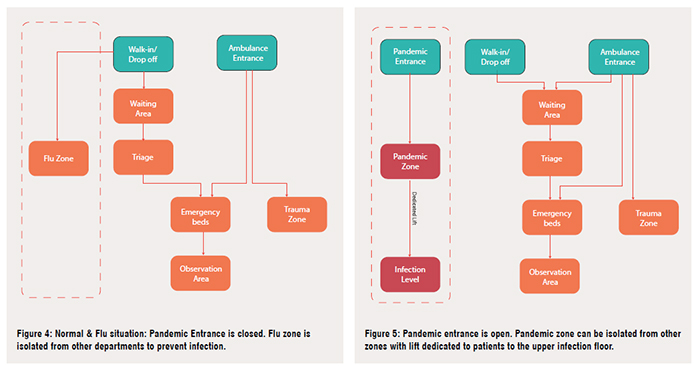

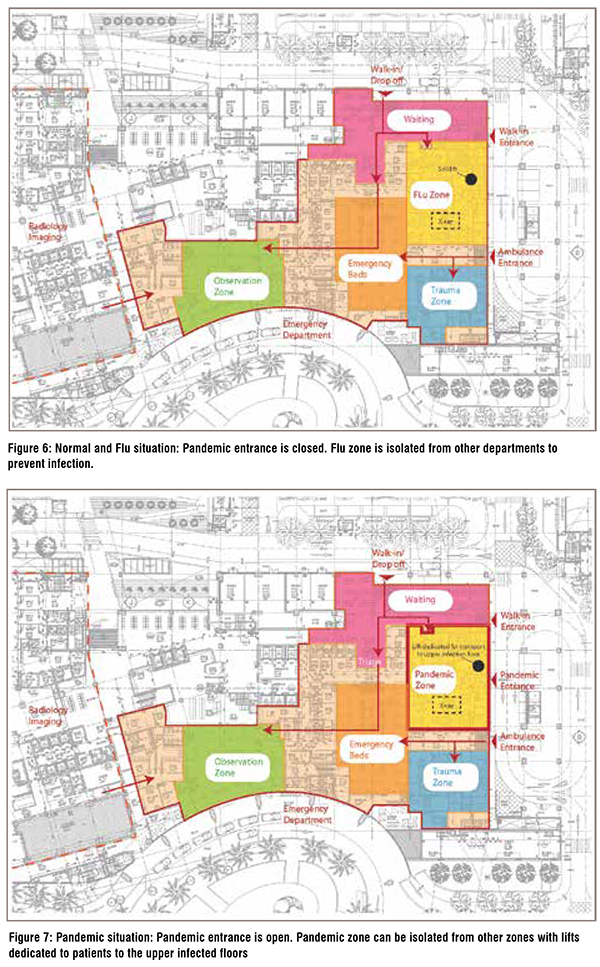

The Emergency department was designed to operate under normal circumstances with 6 key zones including a Fever Clinic, multiple floors with 23-hour emergency observation, Level 1 Trauma/resuscitation rooms, Level 2 and 3 emergency room beds, Level 4 and 5 Fast Track/Triage area and dedicated CT and Radiology Imaging services.

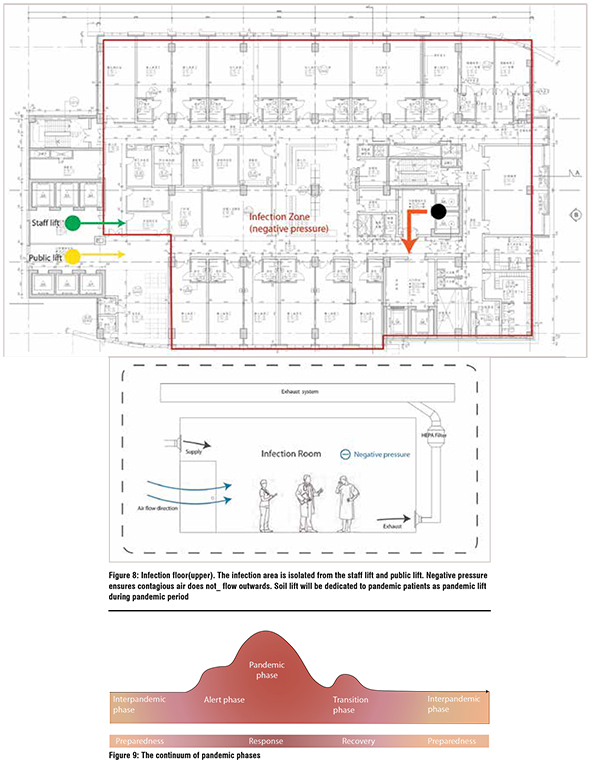

The final design was developed to allow for compartmentalisation into multiple zones which provide isolation and expandability during a mass casualty or pandemic outbreak. The department was designed in such a way to allow for a portion of the emergency department to be isolated for a mass casualty or contagious outbreak, while at the same time allowing for the main emergency department to remain operational. Both the interior of the emergency department as well as the exterior were designed to allow for expansion and compartmentalisation.

Several design features are integral to allow for the expansion of exterior Emergency drop off area into a temporary triage area and separate decontamination area that allows for the treatment of potentially contagious or contaminated patients.

While the physical design and planning of the facility were instrumental in creating pandemic zones within the facility, it was imperative that a mechanical strategy be implemented to compliment the design and provide true isolated zones within an operating hospital. This required mechanical systems which were designed to allow for the compartmentalisation and isolation of several zones during seasonal flu season or potentially pandemic events.

“Silver tsunami” is a term often used in the past decade to describe the rapid increase of people over the age of 60 as compared to the overall population in Western countries, but only recently has the term been heard more and more often throughout Asia.

This trend has created a rising demand for healthcare services for the ageing population, prompting both the public and private sectors in countries across the region to massively expand healthcare and healthcare technology infrastructure.

While designing Chinese University Hongkong Academic Medical Center, a non-pharmacological strategy was adopted for improving the quality of life for the elderly. Outdoor gardens provide a welcome break from sterile healthcare settings and offer elderly residents the choice of leaving the built environment for a natural setting designed to promote exercise and stimulate all the senses. Another aim of therapeutic gardens is to promote ambulation, positive reminiscences, decreased stress and stabilised sleep wake cycles. Exposure to nature has been associated with reduction in pain, improvement in attention and modulation of stress responses. In addition, some studies have reported that having free access to an outdoor area may reduce some agitated behaviours, medications and falls in dementia residents.

Signage and way finding is of prime importance to ensure clarity and reduction in stressful environments for the elderly. We used yellows and reds which stimulate and are good for dining and social areas on the patient floor. As one ages, it gets harder to tell apart blues and greens than it is to tell apart reds and yellows. Regarding interior colours, unsaturated and washedout colours will be avoided in the environments for older adults, as it is difficult for them to discriminate these colours and colour confusion may result in falls. In addition, an appropriate contrast between colours of the wall and the floor, and floor surfaces at different levels emphasises the edges of spaces and help older adults distinguish features of the environment at the CUHK Hospital. A homelike environment for the design of the rooms enhanced the belief that people should be able to age in the same way they are accustomed to living.

Change is inevitable in a healthcare facility. It can be caused by a variety of factors:

• Growing importance of chronic disease management

• Changing consumer expectations in the delivery of care

• Rapid advancement in diagnostictools and technology demand with changing space and infrastructure requirements.

Today’s world is looking for a facility that is scalable, adaptable, and modular. It needs to have the ability to expand and contract services based on changing needs, whether that be a daily peak hour or long-term growth. For the Gleneagles ChengDu Hospital we followed this approach:

Universal rooms and modularity

Universal rooms are designed to cover a wide range of care requirements so they can be used interchangeably. The design team studied all patient room requirements to design a set of rooms that can be adapted to each specialty. Rooms are sized in a modular fashion, allowing a future ‘plug and play’ approach in case of changes in patient volumes or expectations. For example, two double rooms can easily convert into one 6-bed room, since they occupy the same space.

Shell space

Wherever possible, a space has been identified that can be occupied by future functions. Its location in the centre of the floor plate and adjacency to the central service corridor will allow it to either serve as future expansion area for the adjacent department or remain free-standing.

Future expansion-Inside the given site boundary of certain projects, no expansion area was available to increase the building footprint. It was important to study vertical expansion with a careful study of existing and proposed structural systems. Areas needed to be cordoned off bearing in mind that hospitals need to continue functioning during the construction process and minimum disruption to existing processes would be allowed at any facility. A thorough study of the hospital’s current operations was done to propose temporary changes while the expansion process continues efficiently. A phased expansion approach is necessary where modifications can happen in an incremental fashion.

Due to constraints in building size innovative ways of managing the anticipated patient volume were required. The design team was especially mindful of preparing for overflow capacity, in each area separately as well as for the department. A few strategies that were implemented to expand the current capacity are as follows:

• Utilise adjacent care areas for overflow capacity. Even though all care areas are designed as independent modules, they all share one department corridor, allowing consult rooms to be reassigned to an adjacent module during surges in another. This strategy can be leveraged to manage seasonal events like flu season

• Utilise alcoves as patient hold areas. Alcoves have been designed in a long linear fashion along corridors, allowing placement of additional recliners or beds in them as needed. These alcoves can be further enhanced by adding medical gases, power points, and curtain. This strategy can be leveraged during busy hours of the department, such as evenings

• Implement low-acuity exam pods.These exam pods are gaining traction in the US and Canada to help manage the volume of low-acuity patients looking for the convenience of 24-hour access to healthcare. Designed as a one-stop shop for triage, blood draw, results waiting, and treatment, they take up significantly less space than a full consult room while still providing all required infrastructure. Patient can enjoy amenities like charging stations and wifi while they wait, not needing to visit multiple areas to complete their visit. This strategy can be leveraged to handle a permanent increase in low-acuity patient volumes.

Important resources during this process included initial feasibility studies, future projections, and area trends, as well as any long-term growth plans the institution had in place. Other resources included the knowledge of frontline staff who can identify areas for improvement or environments where constant change is needed and difficult to achieve. Regardless of how flexibility is brought forth as a design consideration, establishing specific flexibility goals was paramount to a project’s visioning process.