The author, with over a 40-year period of active neurosurgical practice (1975-2015) has personally certified over 2,500 deaths in a government, trust, and corporate hospital in Chennai, India. Retrospectively, the author wonders if, the importance he paid to Quality of Life should have been supplemented with equal importance to good quality of death. This is even more important in 2023. This future ready article will emphasise that the radical transformation of healthcare due to unprecedented growth and development of technology brings with it dangers of dehumanisation. Exposure to end of life and palliative care is even more important now.

This article is to sensitise the readers that in 2023, facilitating a good Quality of Death is as important, as what doctors are normally taught — to ensure a good quality of life. Until six decades ago, death was considered a specific point in time — the moment at which life ends. Today, it is accepted that death is an ongoing process — a series of events culminating in irreversible cardiac arrest. Perceptions of a healthcare Provider towards death, changes as he/she ages. Initially, the emphasis is to prevent death in every patient taking every possible measure. After all saving lives is the raison d’etre for our existence. How often did we then ask ourselves “but at what cost?” With time a major constraint, did we spend quality time with the caregivers of an individual, whose passing away was imminent. Did we discuss End of Life scenarios? We were so engrossed in providing intensive critical care, in adjusting ventilator settings, correcting electrolytes, repeating imaging studies, protecting ourselves by getting multiple second opinions that we hardly ruminated on the Quality of Death. Understanding psychological, social and spiritual needs at this time is as critical, as developing skills in grief counselling.

How does one discuss “good death” with a just married wife, when her husband has had a devastating bleed in the brain? How does one inform a retired Professor of Surgery that he has multiple secondaries not only in the brain but elsewhere and any therapy will at the best only postpone the inevitable. A 92-year-old woman with stroke on both sides is strongly encouraged to be taken home. She also has multiple hip fractures secondary to the trivial fall. Two months elapse. Patient is in coma for four weeks. Morphine patches are being used for analgesia. The 70-year-old son cannot withstand her suffering. After discussion, Ryles tube feeding is also stopped with the hope and prayers that an irreversible cardiac arrest would occur. Alas, the lady has not read text books of medicine. The heart goes on beating for another 48 hours with the elderly children going through an agonising time.

The term Good Death was introduced in the nineteen sixties. A Good Death implies that treatment preferences, quality of life and maintenance of dignity have been as per patient’s desires. There has been no distress or suffering for patient, family and caregivers. There has been little or no pain. The death is consistent with prevailing clinical, cultural and ethical standards. Excessive or futile treatments are not used just to prolong life. There is total trust, support and comfort with the doctor and the nurse. There is an opportunity to frankly discuss all beliefs and fears and to bid farewell to near and dear. When end-oflife is inevitable and patients or their families consent, aggressive therapies, medications and interventions are stopped but care is never withdrawn.

Death and process of dying play an important role in all societies and cultures. Notions of good death are specific, unique, and different. Advances in medicine and technology have resulted in longer end-of-life periods often making the process of dying more protracted. A Good Death is not a single final event, but a series of social events. End-of-life support and care should continually respond in flexible and dynamic ways to the wishes of the dying person. Dying needs to be understood as a process that can be influenced. Though dying is inextricably tied to life, there is a general reluctance to speak about death. A study in 2017, revealed that seven in 10 Americans preferred to die at home, an important component of Good Death. Costs also needs to be factored. Interventions to improve end-of-life care have important ramifications for dying patients and spouses. Sudden events precludes time to discuss end-of-life issues with family members. Terminal illnesses offers time for discussion and resolution of "unfinished" psychological and practical business. Good Death includes not being a burden to the family, leaving affairs in order and having a sense of fulfilment.

A bad death is one in which there is violence, pain, torture, dying alone, being kept alive against one’s wishes, loss of dignity, and inability to communicate one’s wishes. Proper communication makes a difference between good and bad death. Excessive use of technology, with patient and family wishes ignored, contributes to a bad death.

Choosing assisted dying is an incredibly difficult decision for all involved. Judging quality of death is very personal. Assisted dying laws allow patients and families some measure of control over time and manner of death. Switzerland’s law permitting assisted death has been in force since 1942. In 2014, Belgium included children in its 2002 euthanasia law, the same year when the Netherlands legalized assisted suicide and euthanasia. Oregon in the USA has permitted selfadministered doctor prescribed lethal medications since 1997, under the Death With Dignity Act (DWDA). Washington passed a similar law in 2008, as did Vermont in 2013. Eight states in the USA have passed laws allowing doctor-assisted death In February 2015, Canada’s Supreme Court ruled that adults suffering extreme, unending pain would have the right to doctor-assisted death. The South Korean government implemented the "well-dying law" in 2018, which enables patients to refuse futile life-sustaining treatment (LST) after being determined as terminally ill. In a landmark judgement delivered on 9th March 2018, a 5-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India recognising ‘living wills’ made by terminally ill patients, held that the right to die with dignity is a fundamental right. Legalising passive euthanasia Justice Chandrachud had remarked, “Life and death are inseparable. Every moment our bodies undergo change… life is not disconnected from death. Dying is a part of the process of living.”

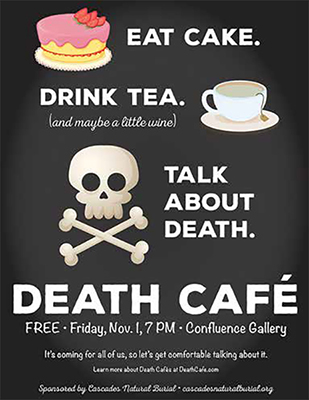

Palliative care extends beyond medical treatment. In many countries, Death Cafés, offers meetings over tea and cakes where participants can hold open conversations on death, sharing ideas and concerns. The Death over Dinner movement suggests groups of friends host dinner parties to process how they feel about death. “How we want to die,” the movement’s website prompts, “represents the most important and costly conversation America isn’t having.”

India has been ranked 67 out of 80 countries on the 2015 Quality of Death Index, lower than South Africa (34), Brazil (42), Russia (48), Indonesia (53) and Sri Lanka (65) but above China (71). People in the United Kingdom get the best end-of-life care, according to the index; calculated by the Economist Intelligence Unit. In recent years policy interventions and public engagement to improve quality of death through provision of high-quality palliative care have gained impetus. Recent legislative changes, have made it easier for doctors in India to prescribe morphine. Recognising that most individuals are uncomfortable to talk about death, it has been stressed that Quality of Life ‘Die-logues’ Needs to Include Quality of Death and End-of-Llife care discussions to increase public awareness.

Though the Supreme Court of India in 2018 ruled that “the right to die with dignity is a fundamental right” the implementation and execurion of a Living Will (LW) is still mired in controversy. At present a LW has to be written by the Executor with 2 independent attesting witnesses. This is then countersigned by a Judicial Magistrate First Class (JMFC). The jurisdictional JMFC supplies the LW to the concerned authorities and informs immediate family members. The Hospital Medical Board where the patient is admitted certifies the instructions, informs the Collector who constitutes an independent Medical Board (MB) . This MB visits the hospital and if concurring with the previous MB, endorses the certificate to implement the LW instructions. This MB then informs the JMFC who after visiting the patient and examining all aspects, authorises implementation of the MB’s decision. If life support is withdrawn, JMFC will inform the High Court who shall maintain requisite records in digital format. If there is a difference of opinion between the MB and family members, parties can prefer a writ petition in the concerned High Court decision shall be final and binding. The Supreme Court of India on Nov 23 2022 heard a petition on these ‘unworkable guidelines’. The case has been adjourned to Jan 17th 2023.

The last two decades have witnessed an unprecedented deployment of technology in Healthcare. Younger clinicians are super-efficient in what they have been trained to do, but somewhere along the line are we missing the wood for the trees. Is it not in their ‘job profile’, to also be responsible to ensure a good death for patients, when death is inevitable. Are we too busy, to commiserate with the family, empathise, sympathise with the individual who has placed his/her life in our hands.

Textbooks, journals, clinical meetings and group discussions can give us guidelines and scientifically valid statistics of different outcomes with different management plans. How often do we factor in the specific desire of the patient? Are we totally transparent during our counselling sessions. Unconsciously, inadvertently is our approach influenced because we are on a ‘fee for service’ or on a salary. Should society's healthcare resources be directed primarily for ‘curing,’ or ‘caring,’? When is enough enough for the terminally ill? Who decides? Should decisions always be ased on irrefutable scientific evidence and available technology? Do increased ‘options’ only compound the issue. Having been involved in hundreds of deaths during a full professional career, one sometimes becomes less sensitive. We forget that for the aggrieved family it is often the first experience.

Working in a public hospital in the late seventies the author has on several occasions encouraged the family to take a sick moribund patient home so that the septuagenarian would have a good death. Influencing factors included logistics of transporting a dead body across interstate check posts and the costs. Do treatment protocols, algorithms and flow charts give adequate weightage to what the patient and the family wants. Even if “Primum non nocere” is considered, it is generally about the physical body. Do no harm rarely extends to the emotional and economic domains. Discussion of end-of-life management scenarios often has to be initiated within days or even hours of admission. The situation is more complex as the moribund patients were probably in good health before a totally unexpected catastrophe struck. Discussing death should not be considered macabre, ghoulish and in morbid taste. As clinicians, it behoves us to strive to achieve at least a Good Death for all those who have placed their trust in us.

On January 25th 2023 the Supreme Court of India, accepting the appeal that the earlier guidelines were “ unworkable” and that in the preceding four years there was not a single request for passive euthanasia in spite of the 2018 ruling, have relaxed some of the requirements. Hopefully the implementation and execution will now be less cumbersome.