Healthcare requires a revolution in the way we deliver care by utilising IT in new and innovative ways. Path innovation allows experts to work together in the development of workflows that best leverage HIT.

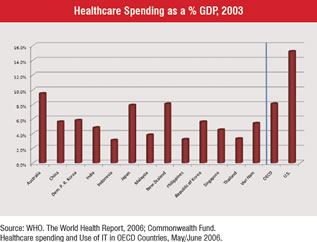

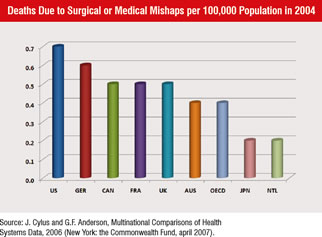

No country in the world spends more of its GDP on healthcare than the US Compared to other countries in the Asia Pacific region, the US spends anywhere from 33 to 500% more, and when compared to other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries it spends 50 to 100% more (Figure 1). Yet according to a report published by the California Healthcare Foundation in May, 2007, the US ranked last or next to last on 9 of 10 measures of healthcare delivery. On the measure of deaths due to surgical or medical mishaps, the US experienced about 75% more deaths than the average OECD country (Figure 2).

Don Berwick, an international leader in healthcare quality improvement observed that “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” Building on Dr. Berwick’s notion, other experts have defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

Perhaps for some of us, deployment of healthcare IT is our expression of insanity. Many organisations, led by dedicated and intelligent professionals, successfully implement—as defined by technical specifications—a variety of healthcare information systems only to discover that their process and outcomes measures change little. Unfortunately, without changing the underlying processes and workflows that existed before the implementation of healthcare IT, little change in those measures should be expected.

Revolution is defined as a “drastic and far-reaching change in ways of thinking and behaving.” Healthcare systems require a Health Information Technology (HIT) revolution, a drastic change in the way we deliver care by utilising IT in new and innovative ways. Aggressively deploying IT, to replicate the processes and workflows that currently deliver disappointing results on so many measures, only guarantees continued sub-optimal and unacceptable outcomes.

Touted as a source of great efficiency and effectiveness, information technology currently offers limited healthcare examples of significant and documented gains. Considering the millions of dollars spent on healthcare IT by organisations around the world, these results are quite discouraging. To best understand why our gains from IT investments have not materialised, let’s look at other industries as models.

Early investment by other businesses in information technology delivered very unsatisfactory results through the early 1990s. Executives, expecting computer systems to provide increased efficiencies and worker productivity, realised few, if any, benefits from investing is these systems.

The idea of a paperless office never materialised as many workers printed out each and every email message, handling correspondence as they would a mailed letter or an interoffice memo.

Then sometime in the mid-1990s, that all changed. Rather quickly, over a three-year period, using computers to communicate, transact purchases and transfer documents became normal business practice. Developers and users together conceived more and more activities that could be conducted online.

Across most industries that deployed IT, a lag period occurred where quality and costs savings did not appear. As frustrating as this period was, companies that continued to invest in IT, slowly began to experience the jumps in productivity and profit that were long expected. Each organisation reached a tipping point where processes and workflow evolved to take advantage of the new IT tools to deliver unprecedented results. To look at the benefit of IT on these companies in isolation is to miss the true lesson to be gained from their experiences. Early on, the deployment of IT was viewed as the solution. Only after companies recognised it to be just a tool, did they formulate the real solutions based upon revised processes and workflow which then provided much of the benefits.

Revolutionary HIT requires a focus on three key areas: 1) processes and workflows, 2) information technology tools and 3) healthcare provider tasks, duties and responsibilities.

Solutions come from an indepth understanding of tools and creative thinking around what healthcare professionals can do and how best to use their individual skills. Bringing together experts in clinical medicine, information technology and process redesign creates an environment where the best processes and workflows effectively leverage the new HIT tools. Such diverse working groups allow meaningful knowledge transfer and the development of solutions that transcend the expertise inherent in each silo of knowledge.

The failure of clinical IT tools to deliver safer and more efficient care is due to many factors; yet all of them have origin in the concept inherent in the phrase “path innovation.” Although the theories and expertise that form the basis of path innovation are not new, their interaction with and subsequent impact on clinical IT is.

Path innovation is dependent upon three key factors: 1) Process improvement or re-engineering, 2) Clinical guidelines, clinical paths and evidence-based medicine, and 3) IT system design. Although subject matter experts exist in all these areas, it is unclear how well these experts historically worked together in the design and implementation of clinical IT systems.

Process improvement experts understand how processes impact outcomes and what analytical steps are needed to evaluate processes. They are able to suggest changes in processes and predict the potential improvements such changes will deliver. Experts in clinical content understand what various clinical paths deliver as outcomes. They are able to link various interventions with probabilistic results.

Designers of IT systems understand the flow of digital information within computer systems and the user interfaces that receive and deliver data to users. They are able to conceptualise how a data point can be stored or reformatted with other data points.

Almost universally, these experts work and apply their expertise independently of each other. IT system designers develop clinical IT systems using specifications developed by product managers who attempt to bridge IT with healthcare. These product managers are rarely experts in clinical medicine or clinical processes. Clinical content experts develop clinical content focussed solely on clinical issues, rarely incorporating IT system design or clinical process considerations in their work. This is evident in the effort invested by many organisations to modify existing guidelines to fit their newly implemented clinical IT systems. Their reported struggles are indicative of the difficulty of this type of work.

Process redesigners often appear on the scene late in implementations, if at all. Working within the environment as presented to them, they try to change existing processes without the advantage of being able to change the inputs (e.g., clinical path) or tools (e.g., clinical IT system and its functionality) of the processes.

To implement and effectively leverage clinical IT systems, a new approach in the use of experts is required. Path innovation integrates different subject matter experts in unique ways to leverage their expertise throughout the design and implementation of clinical IT systems. Even for systems already built, path innovation can be used to better leverage existing functionality in these clinical IT systems. It can help enhance outcomes while reducing the probability of unacceptable results such as system related medical and medication errors.

Path innovation requires the formation of a team of subject matter experts that apply their skills during an entire clinical IT system project. During the system design phase, clinical and process design experts share their understanding of their discipline with the IT system developer.

During the implementation phase, the IT system designer and the clinical content expert act as consultants to the process redesigner to develop new processes that are both radically different from existing processes and that could only be implemented utilising functionality made available by the new clinical IT system. In addition, the clinical content expert can use this functionality to conceive of clinical paths impossible without this digital healthcare capability.

Although path innovation builds upon existing approaches, it reflects a new way of thinking and approaching problems. Instead of looking at how an existing process could be modified, path innovation requires the birth of brand new processes, formerly impossible in the institution before the installation of the new clinical IT system. To accomplish this, organisations need to identify subject matter experts who are also able to achieve a basic understanding of the disciplines of their expert colleagues. Then together, these experts work to create new processes that incorporate the needs of the institution with the promise of new IT systems and clinical content.

Valued solutions offer these professionals HIT tools that leverage their unique skills, while organising the processes and workflows to deliver a consistently high quality, safe and efficient healthcare outcome.

Inherent in revolutionary HIT is the need for change; change in what professionals do and how they do it. Therefore, effective change management techniques must be utilised to facilitate the acceptance of the new processes and workflows, in addition to any new responsibilities and duties.

Currently patient delivery relies upon an unreliable system of poorly integrated and highly variable healthcare professionals. Revolutionary HIT solutions provide needed support tools that increase the reliability of the human components, while integrating these components through effective processes and efficient workflows.

Revolutionary HIT fundamentally changes what physicians, nurses and other healthcare professionals do. Physician activities become more challenging on a cognitive level as other routine tasks such as drug dose recall, use of best practice order sets, and drug-allergy checking become automated. Physician expertise is assigned to more important tasks including solving difficult diagnostic problems, devising customised patient treatment plans, and influencing patient adherence to chronic disease care regimens.

Work for nurses and other healthcare professionals changes dramatically too. These professionals, guided by intelligent processes and workflows that include meaningful HIT, complete more tasks formerly done by physicians or other healthcare specialists.

Revolutionary HIT places the right professional, with the right knowledge in the right process, utilising the right workflow to d liver the best evidence-based care to the patient. Care delivery

is focussed on the patient and their needs rather than the requirements of unchanged, ineffective workflows established before the dawn of information technology.

For information technology to play a valuable role in reducing healthcare costs while enhancing quality of care, it must be deployed in a revolutionary way that completely reinvents how care is delivered, professionals provide the care, and technology is leveraged throughout care delivery. In addition, if we embrace path innovation, and incorporate it proactively into our deployment of healthcare information technology, we will then be able to accrue the huge increases in quality, patient safety and efficiency we expect from these revolutionary tools.