A recent analysis showed that one fourth of all ischemic stroke cases can be labelled as fake strokes. Furthermore, one out of four is treated as an acute stroke with a very good outcome, but severe complications occur in the minority of them. It raises the need for proper staff education as well as the inclusion of sophisticated brain imaging.

Ischemic stroke (i.e., a brain vessel occluded by a blood clot) is the leading cause of disability and one of the leading causes of deaths worldwide. There are effective strategies in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) including systemic thrombolysis and endovascular procedures. Systemic thrombolysis means intravenous application of a thrombolytic (clot busting) agent to restore cerebral blood with subsequent improvement or resolution of neurologic deficits (clot busting therapy). Thrombectomy involves artherial catheter insertion (thin tubes visible under X-rays) through the groin or the arm to reach the occluded vessel for clot removal (similar to the procedure in the case of myocardial infarction). There is a limited time window to carry out these procedures (usually 4.5-6 hours for systemic thrombolysis and 6-9 hours for thrombectomy, although exceptions occur) as their efficacy is time-dependent (time-is-brain concept), therefore shortening time window (from admission to procedure) is crucial in the emergency department. Enormous efforts have been recently made to improve the clinical outcome of stroke patients including testing up comprehensive stroke units and the increased availability of hyperacute stroke treatment and shortened procedure time also have lead to inappropriate inclusion and treatment of so-called ischemic stroke mimics (ie. non-stroke patients).

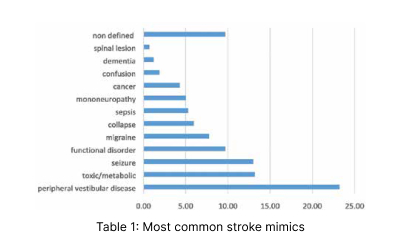

A recent systemic review and analysis (in-depth and detailed summary of the existing medical literature) including the data of 61 studies with more than 62.000 participants showed that approximately one-in-four stroke calls in the emergency department is inappropriate. Fake stroke calls and admissions (stroke mimics) most likely include patients with vertigo/ dizziness, patients with intoxication or severe metabolic disturbances (hyperglycaemia, sepsis etc.), epileptic seizure with subsequent limb weakness, psychiatric disease (functional disorder) and complicated migraine (headache with preceeding neurological symptoms such as visual disturbances or slurred speach) as can be seen in Table 1.

Vertigo/dizziness is a common complaint of patients seeking medical attendance, however, stroke syndromes are responsible for only 3–5 per cent of all emergency cases. In the case of acute stroke dizziness/vertigo usually accompanies other neurological symptoms and signs but it can be challenging. Interestingly, detailed head imaging including perfusion techniques (see below) are not as sensitive as simple physical manouvre called HINTS test (Head-Impulse—Nystagmus—Test-of-Skew).

Metabolic/toxic disturbances were the second most common cause of stroke mimics in the mentioned comprehensive review. These are usually detectable in the laboratory, but the lack of detailed blood test results is not an exclusionary criteria based on current guidelines (taking blood sample is mandatory, but clot busting therapy can be carried out before blood tests can get ready to shorten procedure time).

Seizure has been recognised as a cause of postictal paresis (subsequent weakness to epileptic seizure) since the 19th century. Postictal dysphasia (speech disturbance) has also been reported to follow dominant hemisphere seizures. If a previous seizure is unwittnessed these symptoms are easy to misdiagnose as a stroke or a transient neurological symptoms of vascular origin. Although seizures can occur due to ischemic strokes, especially in cortical lesions, but these are rarities, the presence of a seizure usually implies other etiology than ischemic stroke.

Surprisingly, an underlying psychiatric disease (so called functional neurological disorder) is also a great imitator of ischemic stroke responsible for a significant number of fake stroke calls and admissions. History of psychitaric disease is usually common in these patients, neurological symptoms (weakness, speech disturbance etc) are usually atypical and fluctuating. Physical examination usually shows inconsistent findings with repeated examinations as concluded by the authors. Interestingly, a simple manouvre called Hoover sign – which means weakness of voluntary hip extension with normal involuntary hip extension during contralateral hip flexion against resistance – can be very specific in the diagnosis of functional stroke mimics.

Migraine can also be a great imitator of stroke. Complicated migraine (so called migraine with aura) can be challenging as headache occurs after the presence of neurological symptoms (most likely visual disturbances, numbness and tingling, but speech disturbances or rarely one-sided weakness can also occur). Careful patient evaluation including questions about previous similar symptoms as well as the application of perfusion techniques are usually required (see below).

Sudden onset of neurological symptoms also can develop in patients with intracranial tumors and primary intracranial malignancies may require extensive diagnostic workup including sophisticated head imaging as routine procedures (plain head computer tomography) can be misleading (false negative).

Apart from the above mentioned etiologies collapsing/presyncope, mononeuropathy, acute confusion, dementia and spinal lesions are less common stroke imitators. These are usually easily detectable, but it can be challenging in the minority of cases as concluded by the authors.

This analysis also showed that approximately 25 per cent of stroke mimics can be thrombolysed (clot busting therapy) so they receive conventional stroke therapy which can be associated with severe complications as major bleeding. Stroke mimics had very low overall intracranial bleeding and mortality rates comparing to ischemic stroke individuals and had more favourable outcome, which is not surprising as symptoms were not of cerebrovascular origin.

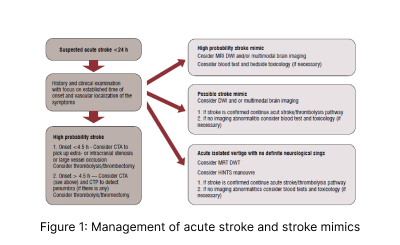

The explanation of these findings is partially due to the fact that ischemic stroke is usually an exclusionary clinical diagnosis in the emergency room. The differential diagnosis of ischemic stroke (so called ischemic stroke mimics) is an umbrella term rather than a single disease. As rapid diagnostic accuracy is required due to the ‘time-is-brain’ concept, sophisticated brain imaging, which can delineate arterial occlusion from other etiologies including seizures and complicated migraine such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or multimodal brain imaging (perfusion CT or MRI) are sparse even in pending situations to avoid significant delay in revascularisation.

Secondly, rapid assessment are attributable to the involvement of emergency staff as first contact who are not properly trained in the detection of stroke mimics, and the relatively low specificity of currently used stroke scales. Potential emergency management of stroke and stroke mimic patients can be seen in Figure 1.

So the set up of comprehensive stroke centres including multimodal brain imaging as well ass strict attachment to guidelines and the training of staff may help to avoid the unnecessary admission and treatment of stroke mimics. The United States is a front-runner in stroke management, however, results of the Get With The Guidelines–Stroke Registry showed that about 3.5 per cent of the treated patients can be labelled as stroke mimics and 2/3 of them had no definite diagnosis on discharge. Furthermore, they have found an overall trend of treating fake strokes in recent years.

The evaluation of stroke mimics merits further investigation and possible modification of the current guidelines.